by Graeme Lehman

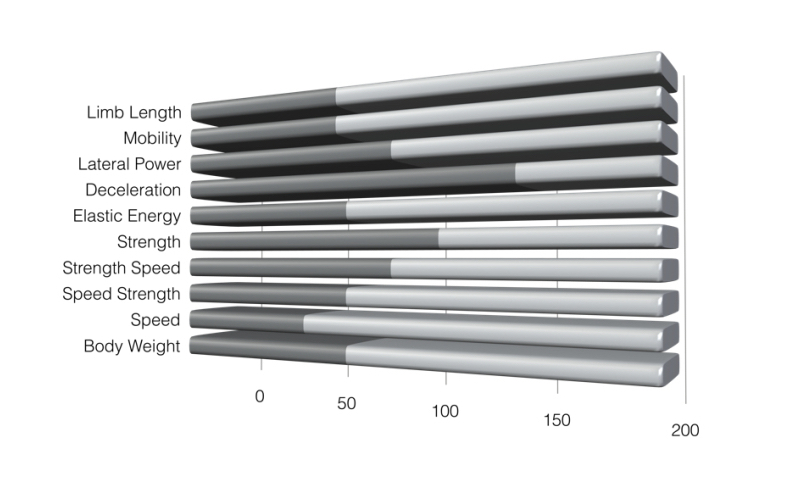

Today we are going to start talking about assessing what kind of engine each pitcher has under the hood and how it plays a role in customizing mechanics. Going back to my race car analogy that I’ve used in previous articles in this series we can think of the first two traits, limb length and mobility, as the car frame and model. These give us an idea of what kind of car we have to work with while the rest of the profile lets us know what kind of engine we are dealing with how much horse power it can produce.

The rest of the traits on the physical profile not only tells us how much force they can produce but more importantly how they produce it!!

We saw evidence of this when we looked at two very different pitchers, Stroman and Sanchez, in part 1 who produce 95 mph worth of horsepower but they go about it very differently relying on their strengths as an athlete. The goal here is to tailor mechanics to suit the athlete and the kind of force they can produce rather than forcing the athlete to adapt to cookie cutter mechanics.

What’s more exciting is that the engine an athlete currently has can be improved through proper training to enhance their areas of strength’s while also addressing areas of weakness. This means that the engine building process is adaptable. The secret is getting each athlete to adapt to the right kind of training.

The number of physical traits on the profile makes it easy to see how there are thousands of different options when it comes to designing a training program for each player with their own unique profile. For example, some guys need to stretch their muscles to create a larger range of motion while playing long toss and performing a well-designed plyometric training program to develop speed.

While others would benefit more from doing specific drills to learn how to control their entire range of motion and placing more emphasis on traditional weight room exercises to gain both size and strength. The secret is finding the most effective and efficient way through the 1000’s of options which is the exact reason we need to test and assess each athlete in a variety of tests that give us a broader sense of their muscular system.

So lets get started and explore the physical trait of “Lateral Power.”

—

Lateral Power

The ability to produce power in a lateral direction is a key performance indicator (KPI). Sure I am might be a little biased since this was the topic of my thesis but I just merely backed up what smart people in the baseball performance industry already knew to be true anecdotally. If you want to learn more about this read my interview with Eric Cressey who was one of those smart people I was talking about.

In business KPI’s are described as quantifiable measurements that help track success. If you are in the business of throwing hard then its in your best interest to track and measure your ability to jump laterally off of your right leg towards your left (switch if you’re a south paw). The reason that you want to do this is because it is the best test that you can use without any equipment other than a tape measure to help determine your ability to throw hard.

The lateral jump out performed all of these common and not so common tests that I ran 40+ college baseball players through for my study.

> 60 yard dash

> 10 yard dash

> Medicine ball squat & throw

> Medicine ball scoop & throw

> Vertical jump

> Single leg vertical jump R&L

> Hop & Stop

> Broad jump

> Triple broad jump

> Ten yard hop test

The goal of the study was to simply see if any of them correlated to higher throwing velocities and the lateral jump was the hands down winner. It’s not to say that all of these other tests aren’t useful because most of them are valuable. A lot of them will be discussed in the next couple of articles because of the information that they provide in developing a better picture of other of muscular traits and the type of engine an athlete has to work with.

—

What’s the Test?

Stand on your right leg and mark the inside of that foot as the starting point. Load up on the right leg and jump as far as you can to your left while landing on both of your feet. Both feet have to land at the same time and can be no further than a couple of inches apart. Mark the outside of your right foot and measure the distance to the starting point.

—

How Far is Good?

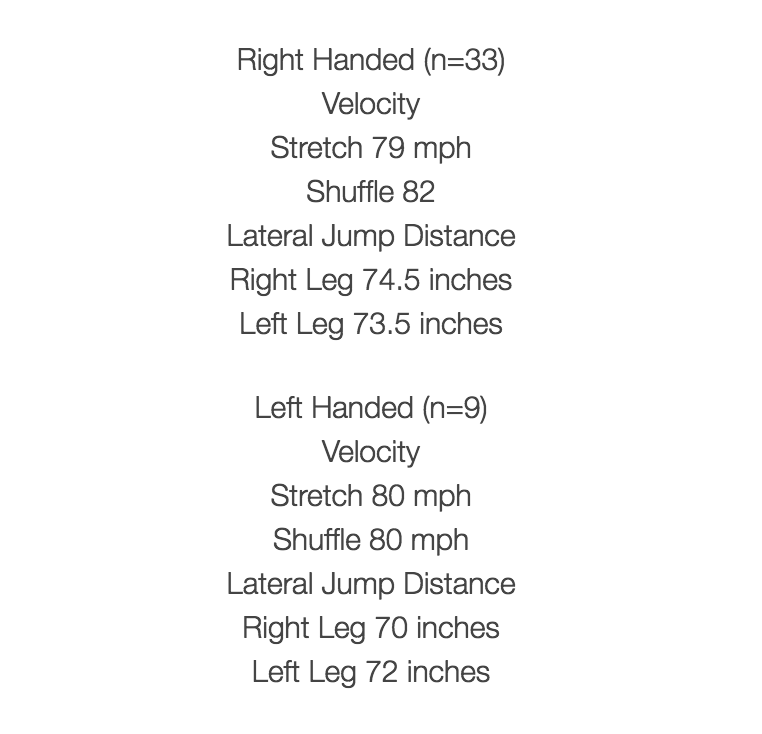

Here are the results from the my study. I have some more number from other athletes I’ve tested in the past but this one was obviously the most accurate in regards to the testing conditions and repeat-ability. I encourage you to play around with this test yourself but let’s use these numbers to start.

—

How to Use This Information?

The simple way of looking at it is if someone can jump out beyond 74 inches but can’t throw harder than 80 mph then that guy needs to work other parts of his mechanics because his throwing velocity isn’t reaching its potential based on the amount of force he can produce from the back leg. There’s lots of power coming in but not much coming out which means that there is a leak somewhere up the chain!!!

In a study back in 1998 by MacWilliams et al. they found that while there was a high correlation in the amount of force that the back leg produced and throwing velocity that there were cases where more force resulted in slower velocity. Not everyone is going to be able to handle the forces like Carter Capps’ does with his mechanics that produce high 90’s stuff.

We also know that the front leg produces the highest forces making it the limiting factor. If your front leg (aka the brakes) aren’t strong enough to handle the amount of force that the back leg (aka the gas pedal) can produce then bad things are going to happen. You should only drive as fast as your brakes can handle for pure safety reasons. We will talk in depth about the brakes when I discussed deceleration and eccentric strength.

The ability to laterally jump far only means that you have a lot of “motor potential” for throwing hard. Motor Potential is term that in his book “Special Strength Training Manual for Coaches” Dr. Verkoshansky, one of the best sport scientist in history, describes as :

The muscular capacity to produce the greatest quantity of mechanical energy per unit of time

Throwing a baseball hard requires producing a lot of energy in a very short amount of time but Dr. Verkoshansky goes onto to talk about the importance of what he calls “technical mastery” which he describes as

The athlete’s skill to effectively express his motor-potential in competition

This brings us to the situation where an athlete can throw harder than 80 mph while not being able to jump further than 72 inches. This athlete can be considered to have a high level of “technical mastery” This athlete is transferring a high amount of force from the back leg all the up to the ball but when there isn’t enough force to start with there isn’t much you can do. Spending more time developing lateral power and increasing motor potential with this athlete would be a better use of time and resources, namely time and energy. Increasing ones lateral jump is a subject that I will touch on when we explore the other traits of the physical profile.

—

New and Improved Test!!

While the lateral jump test is great I have been trying to find ways to make it better. Here are a couple of ways that I have adapted how I test and record the Lateral Jump as I’ve continued to learn myself.

—

Add POWER?

If all we did was look at the distance each player could jump we would be missing out on half of the equation that makes up the kind of power than we are interested in measuring. Looking at the distance gives us an idea of how fast an athlete is because of the fact that jumping requires muscles to produce as much force in the shortest amount of time possible, think back to the motor potential description above.

“Body weight is always a contributing factor to throwing velocity and in fact it was right up there with lateral jump distance as being the best predictor of throwing velocity.”

The other half of the equation for power is force which is the mass/body weight of the pitcher. I’ve spoken at length about how important it is to look at vertical jump POWER by taking body weight into consideration by using formulas that sport scientists have produced since not many of us have access to expensive force plates.

Body weight is always a contributing factor to throwing velocity and in fact it was right up there with lateral jump distance as being the best predictor of throwing velocity. So it would be obvious to combine these two tests into one super test!

The problem is there isn’t one to my knowledge and I haven’t had much success when I try to use the formula for vertical jump since the two types of jumping are very different. I have however came across a formula designed for the broad jump in a conversation I had with Dr. Bryan Mann who is another name you will hear me talk about in the near future because he is the world’s top expert on velocity based training. If you haven’t heard of him it’s because the velocity we are talking about is barbell speed rather than ball speed.

Since this new formula is designed for a horizontal jump it does a lot better job of giving us an idea of how much POWER a player can produce going laterally and horizontally. It’s not perfect but better and if anyone does know of another formula or has access to a really expensive force plate that can measure force in every vector let me know. I’ll talk more about this formula and my spread sheet that I have been building to help build these profiles when I sum up this series.

—

It’s All in the Hips!!

To take this test a step further and make it even better I am going to steal a concept I learnt from Kevin Neeld. Kevin is one of the world’s top authority in training hockey players and since I live in Canada I deal with a lot of hockey players and I have really found Kevin’s blog to be a top resource, check it out here. Hockey is another sport that is seeing the value of the lateral jump since it shares many more traits to the skating motion than either the vertical or broad jump making it the most specific to the sport.

Kevin is a very smart guy and he took this test to a whole new level by taking into consideration other factors that could affect the test result of a lateral jump. He highlights these three areas:

> Limb length

> Flexibility

> Hip structure

I will quickly go over these but check out his blog post about the subject to get a better understanding.

Limb length

It’s easy to see how having longer legs would make it easier just to step rather than jump side ways which doesn’t do a good job of seeing how athletic that player is. So by taking this distance into consideration we can get a better idea of how far each player can jump relatively to their leg length.

Flexibility

It also makes sense to see if maybe someone has really tight groin muscles and can’t even spread their legs apart making this test difficult for them because of a mobility issue.

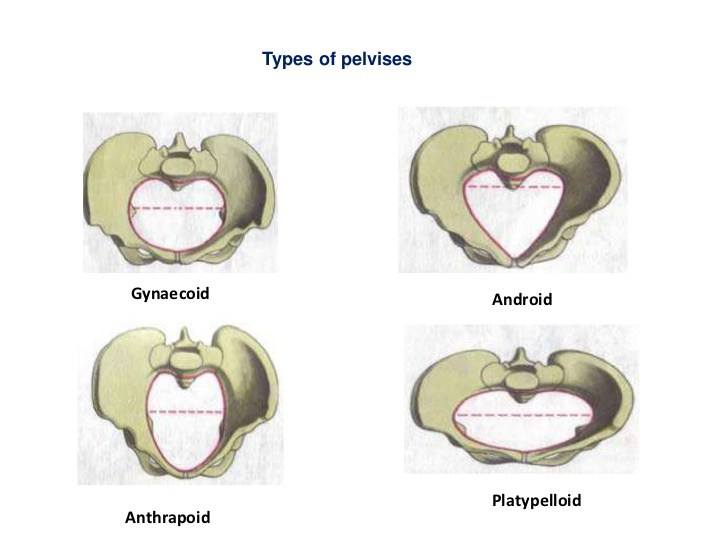

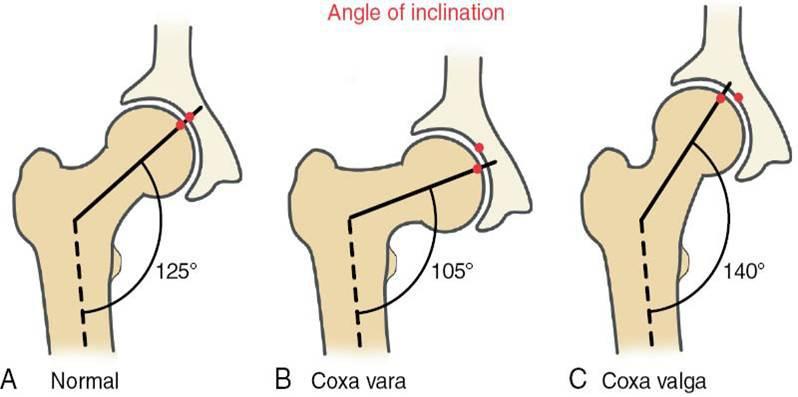

Hip Structure

What was really interesting is how Kevin goes even deeper to think about hip structure because they aren’t all built the same and some are designed to move laterally than others. Check out the different pelvic types as well as femurs to see how the hip joint can be very different from one person to the next.

—

While it isn’t really feasible to see exactly what kind of hip structure each player has it is an interesting topic. Check out this quick preview of a lecture from Dr. Stuart McGill where he highlights how different people from different areas of the world have different types of hip structure and how some hips are made for squatting while others are better designed for sprinting. Take the 4 minutes to watch video to see the importance of this kind of information.

—

The Neeld Hip Factor Test

The test is simple – how far can you can each athlete spread their feet apart while not having their hands on the ground? Check out Kevin’s blog for how he puts this number into an equation to get an adapted score. The beauty is that your score here will be the result of which out of these three factors limits you most.

Seeing how wide a player can stand with their feet apart I think is a great idea for pitching coaches to do with all of their players. This number can be considered their max distance for their stride length unless you employ the jumping style that Carter Capps showed us before. If someone can’t spread their legs out because of a limitation of limb length, flexibility or hip structure you might not want to tell them to stride 90% of their height. Maybe their hips are more suited for rotation and by striding out further you are restricting this ability to twist and rotate.

—

Bonus: Injury Screening!!

The fact that comparing left and right lateral jump score has the potential to help screen athletes for preventable injuries should actually be considered the main reason why we perform this test in the first place rather than a bonus.

Large discrepancies between left and right could mean that you are more at risk for injuries. Think about a car that can produces more force on one side versus the other. Over time the car frame will begin to break down because of torque from the uneven power production. Sure we will see that most pitchers can jump further from their pitching back leg since they have practiced this movement so much more but if we start to see anything greater than 20% it might set off some red flags.

—

Conclusion

This test is so easy to perform and gives us a lot of information that makes it a no brainer. While it is a good test on its own we are starting to see how things can be improved when we look deeper and take into consideration other parts of the profile and how they interact with one another. We will touch on it again as we make our way through the rest of the profile. Next up – deceleration and eccentric strength which should be another good one. I will try to keep it shorter than this one but thank you for making it to the end!!!

Graeme Lehman, MSc, CSCS

—

Check out Ben’s e-book Building the 95 MPH Body and learn to throw harder by clicking here!