This article is based on my experiences and observations playing in college and professional baseball along with dozens of Dominican and Latin players. This is in no way a criticism, but rather my comparison, of both Dominican and American baseball culture and development. The discussion started with a simple tweet. Allow me to expand further on this tweet, and the implications for player development.

—

The Stats

Even on the surface, the differences between the US and the Dominican Republic are stark. The Dominican is home to roughly 10.5 million people, compared to the 319 million in the United States.

In 2015, 83 out of 750 players on opening day were Dominican (compared to 520 US-born), accounting for roughly 11 percent of the major leagues. To put this in perspective, there is one Dominican big leaguer for every 63,000 people, compared to one American big leaguer for every 307,000. This means that the Dominican Republic produces major league talent at about 5 times the rate of the US.

In the minor leagues, it’s not uncommon to see even higher numbers. By my count, 44% of players in the first two levels of the White Sox minor league organization are Dominican-born, and that number climbs to well over 60% at these early levels if you take into account other foreign born players as well (Venezuela, Mexico, Puerto Rico, etc…).

However you slice it, these numbers are staggering, especially when you consider the sheer amount of resources and coaching available to the majority of American-born athletes.

Many American parents drop thousands of dollars per year on lessons, travel ball teams and equipment in the hopes of advancing their sons’ careers, while Dominican players largely get by without fancy equipment or coaching.

—

Money ≠ Advanced development

If we further analyze the discrepancy based on big league players produced per dollar spent, the numbers are mind-numbing. The average annual adult salary in the DR is just under $5,000, compared to just under $40,000 in the US. Living at or below the poverty line leaves far less, if any, disposable income for equipment, lessons, etc.

Compare this to a dirt-cheap American high school travel team fee ($1,200/year), one $50 lesson per month ($600/year), just one glove or bat per year (~$199) and without even taking into account travel expenses, you’re looking at over $2000 per year per American kid that has even a passing interest at playing high school or college baseball.*

So how does the DR produce MLB talent at 5 times the rate of the US (and pro talent at closer to 10 times the rate), all while spending easily 10 times (and probably more like 20 or 30x) less per year on the athletes’ development?

Either much of the US is doing something very wrong from a developmental perspective, or the Dominican is doing something very right. As you may have guessed by now, it’s actually a bit of both.

Here are my top 4 reasons why I believe the Dominican Republic (and other Latin countries) pump out prospects far better than the US:

*I didn’t have access to quite those types of resources growing up, so I’m not saying you have to spend that much money to develop, but this is overwhelmingly “the norm” for many American kids nowadays.

—

#1 They don’t want it, they need it.

This is just basic human psychology. If your family is struggling at or below the poverty line and you are offered a way to take care of your family for life, wouldn’t you work harder than if you grew up with a relatively comfortable life? Maybe your American parents had financial struggles, but you never had to worry if food would be on the table. Maybe your parents got sick, but you probably didn’t have to worry if they would get proper medical care or risk dying from curable illnesses. Of course, these are generalizations. I grew up far from privileged so I understand that this doesn’t describe every American or Dominican.

A strange thing happens when you flip the switch from want to need. When you want to succeed, you may align your intentions with the long-term goal, but your actions are easily derailed. I want to gain 20 pounds quickly becomes “I’d rather go out with my friends, sleep in and skip breakfast.”

When you need something, you’ll stop at nothing to make that goal a reality. There is no other choice. You can’t slow down, even for a second. In this way, desperation is one of the most powerful motivators.

This is why entrepreneurs talk about the need to live off ramen noodles and struggle for a time, just to understand that feeling. This is why coaches always talk about getting “comfortable being uncomfortable.” Being comfortable is a surefire path towards mediocrity.

I’m not saying every Dominican has an exceptional work ethic, or that every American is content and lazy. But just recognize the average living situations for what they are and the impact it might have on normal human psychology.

But hey, maybe you’re a super motivated American kid. What else sets the Dominican system apart?

—

#2 They focus on developing tools over winning games

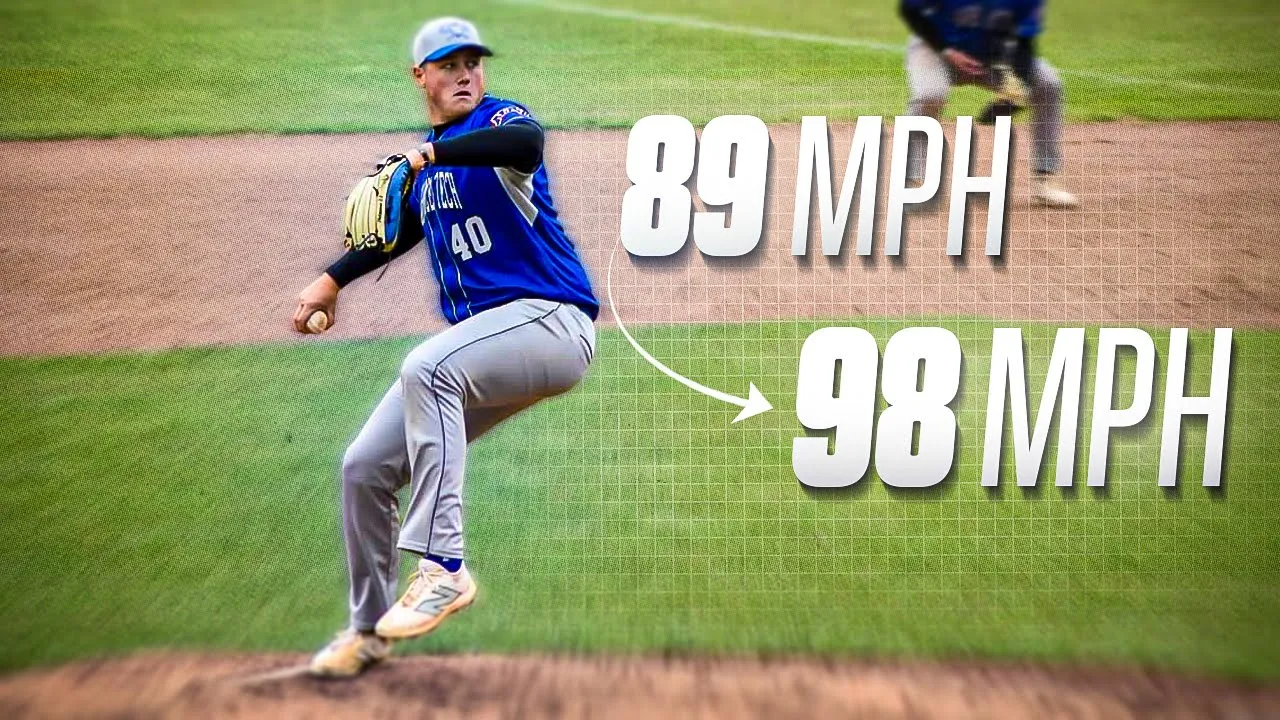

Want to get off the island? Throw with everything you’ve got like your idol: Pedro. Swing out of your shoes to hit dingers like Cano. Everyone is competitive – that’s human nature – but the Dominican baseball culture is tool-centric too. You can’t throw 92 or hit a ball 400 feet by age 18? You’re probably not getting signed.

Pedro the Goat

—

This is why in American pro ball there is almost an expectation of young Dominicans being “unpolished” when they arrive in rookie ball. You see hard-throwing, free-swinging athletes who are a product of this culture. While this is seen by many as a critique, let’s not forget that it got them there, and that it’s rare to see a Dominican in pro ball who didn’t sign for at least $50-100,000, which is potentially life-changing money. They’ve already won, in many ways, just by being there.**

Are these generalizations? Sure. But, bear with me just a while longer all you offended 82 mph strike-throwers.

**While many do, not every Dominican is lucky enough to sign for money. I can recall one instance where a good friend / Dominican teammate didn’t have money to fly home when his mother died during the season. We passed a hat around the locker room until there was enough to send him home for a few days to be with the rest of his family. Still other players would send meal money home to family rather than spend it on themselves, prompting some organizations to just issue meal vouchers to their players instead.

—

#3 Talent hotbeds and motor learning through imitation

An interesting phenomenon that exists in the baseball world is the existence of talent “hotbeds.” In the US, we’re talking about areas like Georgia, Florida, Texas and Southern California that crank out a disproportionately high crop of premium talent year after year, just like the Dominican. While factors like population density and year-round warm weather no-doubt contribute to these numbers on some level, let’s examine it from two additional angles: competition and motor learning.

—

Competition

Both on a micro (team) and macro (league) scale, competition breeds a higher caliber of athlete. As the caliber of players reaches a certain threshold, this creates a positive feedback loop – better players push everyone else to train and compete harder just to keep up (i.e. just to make a Varsity team in high school), which creates even more high caliber players. Furthermore, players who might otherwise be dominating lesser geographical areas can’t take their foot off the gas pedal, or they know that success will be short-lived. An 84 mph high school pitcher may go undefeated in Iowa and, satisfied, stop pushing. That same pitcher in Southern California might struggle just to make his high school’s JV team, forcing him to keep pressing and improving himself.

Side note: as a high school player who didn’t come from this type of hotbed, and where 85 mph meant you were the league ace, it became very important for me to use objective metrics to judge myself against. If I knew the numbers that players at the next level were achieving, I could train for and compare myself against those. I certainly wouldn’t make it if I just compared myself to my current level of competition.

—

Motor learning through imitation

One of the primary ways in which motor learning occurs is through imitation (1). In other words, we can trace back higher level throwing, hitting and other baseball-specific movement patterns to an athlete’s individual expression of the patterns he was exposed to over the course of his development (and in particular, during the very early stages of development, as once the general patterns are learned, these patterns are then further reinforced, and to some extent refined, through repetition).

Put simply, athletes who are surrounded by higher level athletes (and patterns) tend to have a better opportunity and chance of developing higher level patterns themselves. Athletes who are surrounded by non-competitive, low level patterns from a young age are at a massive disadvantage if their goal is to acquire high-level patterns.

Imagine child A growing up in small town America, learning to play catch with the dad below, and only seeing the patterns expressed by other athletes in his intramural little league.

Child B grows up in a minor league locker room, learns to hit and throw with elite players and observes and watches these patterns for a decade. It’s no mystery who will end up with the better patterns 999 times out of 1,000.

This point applies to any baseball hotbed, including the Dominican, but also American hotbeds like those mentioned above. “Excellence breeds excellence” is therefore not only a true statement – it’s science.

—

#4 Other factors

To pretend that these and only these factors account for the differences in US and Dominican baseball achievement would be false. I’ll touch briefly on a couple of these.

—

PEDs / Age Fabrication

While both cultures do have PED-related issues, a larger differentiator is age fabrication, which is extremely difficult if not impossible to regulate for the MLB. However, this practice is well known by pro organizations and most simply don’t care if the prospect is actually 16 or 19 years old if the on-field product is adequate.

I know Latin players who openly share their real names and ages with teammates, but are or were forced to portray a false identity (often by their agents) in order to attempt to be a more desirable prospect to their respective organizations or earn a larger bonus at signing.

—

Anthropometry

Longer limbs/ shorter torsos (or “high butt” as Buck Showalter calls it) may lend itself to better leverages and energy transfer for throwing or hitting. Not only do longer relative legs and arms directly improve leverages, but because the primary function of the torso in hitting/throwing is to stiffen to effectively transfer kinetic energy between the lower and upper half, it’s possible that shorter torsos may also aid velocity via minimizing lost energy during this transfer.

In other words, two 6’4” pitchers are not two 6’4” pitchers. Pitcher A may have a 6’2” wingspan, a long torso, and short legs relative to his height, while Pitcher B may have a 6’6” wingspan, a short torso and long legs relative to his height (potentially more advantageous for throwing/hitting). Scouts have known this for decades, often describing the ideal pitcher’s body as “all arms and legs.” Below is one example of a 6’2″ pitcher with a 6’8″ inch wingspan, followed by a 6’6″ pitcher with a 6’2″ wingspan. Height is therefore just a crude approximation for levers and proportions.

Is this even relevant? Hard to say without data. While there is data showing anthropometric differences, on average, between African, Mexican and Caucasian Americans*, I uncovered no such data for Dominicans, making this possibility purely speculative.

Jeurys Familia (Dominican Republic) and his long levers.

—

*In this particular study on ethnicity and skeletal structure, the authors concluded “blacks have longer legs and shorter trunks than whites, Asians have longer trunks and shorter legs than whites, [Mexican americans] have similar body proportions as whites, but they are shorter.” (2)

—

What We Can Learn from Dominican Success

Let’s summarize what we’ve discussed, and how you can apply it to either your own or your athletes’ development in order to improve your results.

> Learn the difference between want vs. need (easier said than done – if you grew up comfortable and without a fire under your ass, the first step is to figure out your why).

> You don’t need fancy tools (if resources are limited, pour the majority of them into development, not gear, gimmicks and showcases).

> Your pitching/hitting coach is probably unnecessary (again, unless tool development is their priority, stop working on balance points, high cocked positions and towel drills. Train to move athletically and throw the crap out of the ball).

> Focus on tool development over stats/winning games (understanding what scouts and college coaches actually do and don’t look for helps direct training efforts towards those goals)

> Surround yourself with high caliber athletes (if you live in a non-baseball state, consider playing higher level summer ball out of state, visiting elite training facilities, and making sure you’re the softest throwing/weakest person in the room as often as possible).

> Fabricate your age, learn Spanish and get a spray tan (okay, I’m just kidding about this one).

> Understand your body / levers (again, you can’t do much to change this, but understanding genetic advantages/disadvantages is good information to have in building your training plan)

As baseball continues to grow internationally, it raises the collective competitiveness of baseball greatly. Latin American players bring a toolsy swagger to the higher levels of the game that didn’t just appear out of thin air – it’s largely learned behavior, and a good number of American players could learn a thing or two from it.

—

References

- http://www.aaai.org/Papers/Symposia/Fall/1994/FS-94-03/FS94-03-016.pdf

- https://academic.oup.com/jcem/article-lookup/doi/10.1210/jcem.83.5.4844