Loose. Whippy. Free-and-easy. Making it look effortless to throw harder.

These terms have existed in the scouting lexicon for decades as the “uncoachables” for anyone looking to throw harder. You either have it or you don’t –referring in large part to the arm’s ability to lay back up to 180 degrees or more into external rotation before being catapulted forwards into internal rotation at upwards of 7,500 degrees per second.

But why is external rotation so important? And second, can it actually be trained, despite conventional baseball wisdom? Let’s find out.

Billy Wagner’s external rotation, notice the forward trunk flexion and almost 190 degrees of external rotation.

—

Why is external rotation important to throw harder?

Quite simply, increased external rotation provides a greater arc of motion over which force can be applied to the baseball, which allows you to throw harder.. In professional pitchers, degrees of external rotation range from 160 degrees on the low end all the way up to 185 degrees or more. According to a paper by Seroyer et al. (2010),

Extreme degrees of external rotation of the shoulder, coupled with forward linear trunk motion, allow a greater distance for the accelerating force to be applied to the ball, generating top velocity.

Worth noting, not all of this motion is true gleno-humeral “ball-in-socket” rotation – to get Billy Wagner type layback, you’re not just looking at excellent external rotation, you also need:

> Exceptional t-spine extension (to help delay internal rotation even longer)

> Excellent t-spine rotation (to keep the shoulders fully closed, storing energy as the hips fully open into landing – watch Chapman below)

> Excellent scapular posterior tilt (clears room for true ER to occur, and effectively increases external rotation by delaying internal rotation)

> A long history of throwing (humeral retroversion – the actual warping of the humeral head itself, was shown to account for about 10.6 degrees of increased external rotation motion in pro pitchers who have been throwing since childhood)

—

Do you need 180+ degrees to throw harder?

The short answer is NO.

Pro pitchers tend to fall between 160 and 185 degrees of external rotation, so external rotation alone is not the only factor that determines big-league velocity (and velocity is only one piece of actual pitching performance).

.jpg)

Noah Syndergaard doesn’t have the most whippy arm on the field, but he can throw hard.

—

Still, external rotation is one critical component, and most of the very hardest throwers in the big leagues are closer to the upper end of that range.

It’s worth noting that more than this upper range isn’t necessarily better – hyper-mobility beyond these ranges may actually be detrimental to velocity (not to mention potentially dangerous), so be extremely careful seeking extra motion if you already fall in the upper end of this range.“

To the point above, my buddy Mike Shawaryn probably doesn’t need to be working to improve his external rotation:

Remember, external rotation increases the distance over which force can be applied to the baseball, but other factors such as arm length, hip/shoulder separation and shoulder horizontal abduction (sometimes interchangeably called “scap loading”) play a role as well.

It stands to reason that if external rotation is towards the lower end, one can “make up” for it, at least in part, by being excellent at the other qualities that go into mechanical efficiency and velocity (including factors such as raw strength/power).

While there is a lot that goes into it, here are 4 quick ways you can begin to improve your external rotation, IF you are a candidate for it.

—

1) Improve thoracic extension / rotation

Basic assessment: You should be able to lay with a medium sized foam roller under your mid-back with your hands clasped behind your head and get close to touching your elbows and back of the head to the floor without extending through your lumbar spine or your butt coming off the floor. This is a crude test but it is generally enough to give a good first impression of how well (or not) your T-spine extends. For rotation, you should be able to get around 45 degrees (or perhaps slightly more to your arm side) in a seated t-spine rotation test.

If this is not possible, or is highly forced, you’ve got some work to do…

Remember, improving external rotation isn’t really just about external rotation. A big portion of this is having the mobility within the thoracic spine to extend/rotate to gain additional range of motion over which to apply force.

So let’s mobilize those vertebrae.

Once you gain new range, you’ll want to strengthen within that new range. Some examples of this are: properly performed front squats and anteriorly loaded lifts like front rack reverse lunges, and anti-rotation core movements at various angles (such as Paloff Press variations).

—

2) Improve posterior tilt / horizontal abduction

Tightness in the muscles that internally rotate / horizontally adduct the humerus and anteriorly tilt the scapula will inhibit your ability to externally rotate and achieve clean layback.

Case in point: if your pec major, pec minor, lats and subscapularis get tight, good luck having free and easy external rotation.

> Establishing new range: targeting these muscles can be done in part with self-myofascial release exercises like the Pec Barbell Smash, but we have also seen guys have success with partner manual release techniques for the pecs, subscap and lats. These are brutally effective, but outside the scope of this article to discuss.

> Strengthening new range: Again, once full range is achieved (or if you already have full range), you’re going to want to solidify and strengthen that new range in your training. This means full range of motion dumbbell bench presses, full range upper body pulling movements, and a progressively increased throwing program.

—

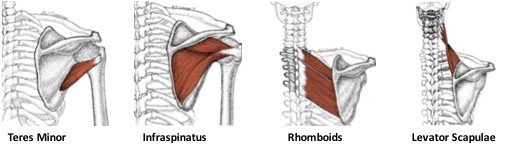

3) Eliminate tissue restrictions on the back side

Though less common than tight muscles on the front side (pec minor, subscap), we have seen examples of external rotation limited by prior injuries or poor tissue quality on the back of the shoulder and scapula as well.

While we recommend seeking out a qualified manual therapist to identify if these exist, here are some areas to be extra aware of (especially if you have a previous injury history of that area or extremely tender trigger points):

> Teres minor

> Infraspinatus

> Rhomboids

> Levator scap

These spots can be pinpointed fairly well using a partner’s thumbs/elbows, lacrosse ball, tennis ball, or Thera-Cane.

—

4) Re-programming movement

Sometimes, tissue restrictions aren’t always the issue from the start, or, even once they have been addressed, external rotation still hasn’t changed substantially.

This is where constraint drills using overweight implements like Plyocare balls and wrist weights really shine. From my 2014 article,

With a heavier object (to a point), there’s more resistance for your arm and body to use as a guide through space and time. You must conserve the momentum of the ball on the arm’s downswing, and efficiently transition and transfer force throughout the arm path to execute the throw with any sort of intent or fluidity.

If you have an egregious timing issue or hitch in your arm path, the heavier the weighted ball, the harder it will be to get away with flaws. The more efficient your arm will have to become in order to propel the object with any meaningful amount of force.

For example, try throwing a football with a long arm swing behind your body or with an inverted-L position at landing – it just won’t happen. Your arm is guided by the constraints of the task (the shape, weight of the object, the target, etc.). In this case, the heavier weight is a very loud and constant feedback loop that makes it incredibly difficult and awkward to have massive arm action inefficiencies.

Additionally, overweight implements help encourage external rotation by driving the arm into layback.

“Note: if the weight of the ball is so heavy that relaxing into the throw is not possible (especially for youth or smaller athletes) back off slightly on the ball weight.“

I don’t use a 2kg on myself for this reason, because I feel my arm tensing up rather than loosely relaxing into layback.

While overload implements are king for remapping external rotation and efficient arm paths, underload implements are king for transferring these newfound paths to throw harder by increasing arm speed and velocity.

Once you have successfully changed your arm path, it may not make sense to spend 90% of your time continuing to throw hard heavy balls at max effort, and may instead make more sense just using them to groove good patterns at lower intensities and volumes. Try devoting more of your time (and higher intensity throws) to the lighter end of the spectrum.

—

Final Thoughts:

You have a tight arm, but it’s not a death sentence to your career or throwing harder. Implementing these four factors may just be the tip of the iceberg, but it’s a damn good place to start. Furthermore, recognize that you will see gains in external just from throwing over the course of the season, so don’t freak out if you are only 5 or 10 degrees off of where you want to be. Also, remember that external rotation is just one of many factors that contribute to velocity, and that not everybody is a solid candidate for seeking more external.

My recommendation… start learning, start testing, and start thinking.

Your career is entirely in your hands.

Check out my e-book Building the 95 MPH Body and learn to throw harder by clicking here!

—

References

1. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ, Escamilla RF. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 23(2):233-9, 1995.

2. Pappas AM, Zawacki RM, Sullivan TJ: Biomechanics of baseball pitching: A preliminary report. Am J Sports Med 13(4):216-222, 1985.

3. Dillman CJ, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR: Biomechanics of pitching with emphasis upon shoulder kinematics. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 18:402-408, 1993.

4. Werner SL, Fleisig GS, Dillman CJ: Biomechanics of the elbow during baseball pitching. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 17:274-278, 1993.

5. Feltner M, Dapena J: Dynamics of the shoulder and elbow joints of the throwing arm during a baseball pitch. Int J Sports Biomech 2:235-259, 1986.

6. Park SS, Loebenberg ML, Rokito AS, Zuckerman JD. The shoulder in baseball pitching: biomechanics and related injuries-part 1. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 2002-2003; 61(1-2):68-79.

7. Seroyer ST, Nho SJ, Bach BR, Bush-Joseph CA, Nicholson GP, Romeo AA. The Kinetic Chain in Overhand Pitching, “Its Potential Role for Performance Enhancement and Injury Prevention.” Sports Health. 2010 Throw Harder Mar;2(2):135-46.