by Ben Brewster

This post goes hand in hand with this youtube video. Give it a watch after completing this article.

Do perfect mechanics exist? It’s tempting to think they do. Why then, do we see such mechanical differences between the best pitchers in the world? Certainly, efficient mechanics exist. One can hardly argue that any delivery that elicits 100 miles per hour isn’t at least reasonably free of energy leakages. While many commonalities exist between the most efficient mechanics, I would argue it’s impossible to come to an agreement on what ideal mechanics even are given the massive structural and anthropometric variability between individuals.

This is why I make a point for the athletes I coach to study and learn from high level throwers who have similar sizes, proportions and frames to them – it makes little sense to have a 5’8″ athlete study the sequencing of 6’10” Randy Johnson, and vice versa. These are obvious examples where the structures are too different to accurately extrapolate one’s movement patterns to another.

“It’s impossible to come to an agreement on what ideal mechanics even are given the structural variability between individuals.”

Even when you take height into consideration, anthropometry can still be a glaring difference that affects how each individual sequences their body parts – making extrapolation even more confusing if you don’t pick the right pitchers to model after.

Here’s one example.

I went through a period in college where I experimented with some of Aroldis Chapman’s movements, timing and body positions.

It didn’t really work.

The timing was off, and I could never get my arms that far behind my body or properly sequence things using a similar tempo.

Though he’s 6’4″ 225 lbs, and I’m 6’3″ 215 – close on paper – the differences in torso, leg and arm length (not to mention his insane shoulder laxity), made these positions (and more importantly, timing) all but impossible for my own structure to imitate.

What specifically works for Chapman – the timing, sequencing and body positions relative to each other – won’t necessarily work for another pitcher. If it does, they are probably built just like him (take a look at my buddy, Solo, who is similarly proportioned with something like a 6’9″ wingspan at 6’3″ tall).

But there are more subtle ways in which body structure affects mechanics, beyond easily noticeable variables like height and body proportions.

Let’s talk about one such variable: hip anatomy, and how it relates to individual mechanics and velocity.

Examining the extremes

Let’s take a look at a few big leaguers, in no particular order: Fernando Rodney, Justin Verlander, Masahiro Tanaka and Carson Fulmer.

I want you to watch their lower halves – what do you notice?

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see that Rodney and Tanaka internally rotate the rear hip, using this position to load the hips and drive laterally towards the plate, while Fulmer and Verlander externally rotate the rear hip, holding on to a vertical rear shin angle as long as possible while the front leg swings open. Interestingly, their lead legs mirror the rear leg, showing similar internally or externally rotated positions.

Most pitchers are somewhere between these two extremes – the knee-to-knee drive, which requires exceptional hip internal rotation – and the vertical shin drive, which relies on excellent hip external rotation and abduction.

With examples of big leaguers on both ends of the spectrum, it begs the question: which type of lower half drive is more efficient? And if the answer is: it depends, what factors does it depend on?

Understanding your hip anatomy

We all know athletes who have excellent hip external rotation – sitting cross-legged or doing a pigeon pose are no problems for their hips. But put them in any position that requires internal rotation and they’re likely to struggle.

On the flip side, athletes who have large degrees of internal rotation tend to come up short when you test them into external. As you can see below, I wouldn’t exactly be the best candidate for sitting cross-legged as I run out of room very quickly into ER.

So what’s going on here? Why can’t some athletes just mobilize their way to having excellent external and internal?

Mobility work helps to a point, but ultimately you may run into a hard limiting factor: your bony anatomy.

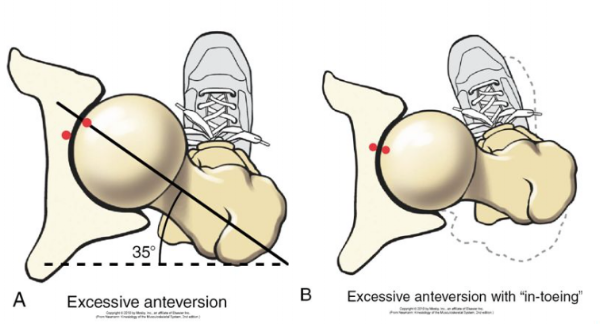

Hip structure can vary in a number of significant ways between individuals, but what is perhaps most relevant to this conversation about rotation range of motion is what’s called hip anteversion and retroversion.

Hip anteversion refers to a bony structure where the neck of the femur is rotated anteriorly in the hip socket. This leads to less ability to externally rotate the hip, because the hip joint has run out of room to move in that direction. In fact, excessively anteverted individuals may walk with their toes facing inwards to better line up their femur in the hip socket.

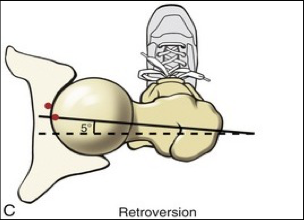

This is measured by taking the angle between the neck of the femur relative to the transcondylar axis of the knee (the horizontal line through the knee in the image above). What’s classified as “normal” is about 15 degrees, so anything greater is considered anteversion – but don’t worry, you’re not going to have to measure this angle.

Hip retroversion is the opposite – the femoral neck is angled more posteriorly in the hip socket, leading to a reduced ability to internally rotate the hip. Excessively retroverted individuals may walk with a toe-out gait to better position their hip joint during motion.

Confused? I know I was.

Here’s a minute of me explaining it in plain(er) english.

Let’s recap.

Everyone’s hip structure is different – so some guys will struggle to move in positions that require more hip internal rotation or relative hip external rotation.

But because extremely hard throwing (and successful) MLB pitchers exist on both ends of the continuum, all hope is not lost if you fall on one end of the spectrum.

It’s about tailoring your movement and your mechanics to what works best for you (specifically in this case about the strategy you use to laterally drive towards the target).

So what? How should I change my throwing or training based on my hip structure?

We’ll leave training for a different article – that has been covered in depth by many in the performance world. Anteverted individuals probably won’t feel comfortable in sumo deadlifts or wide stance squatting, and vice versa. Case in point – find the depth, stance and exercises that don’t create a pinch or bony contact in your hip joint.

For throwing, there’s no reason we shouldn’t take the same tinkering approach to figuring out what works best for your hips.

I had a conversation with Eugene Bleecker last month where he brought up this very point – some guys not only shouldn’t, but can’t throw internally rotated on their back leg. I agree. We had come to the same conclusion independently of one another by noticing that some athletes just don’t get better if you force them all into the same positions.

So here are three ways to actually address the issue:

#1 Test different foot positions on the rubber

Tinker with the foot even with the rubber, turned in about 15-20 degrees, and turned back towards second base about 15-20 degrees. This is a great example of the “intelligent tinkering” strategy. Retroverted guys tend to do best neutral or externally rotated, while anteverted guys (like myself) tend to do best neutral or internally rotated. I’ll actually add a fourth position here as well: hooking the rubber. Testing and gathering both objective and subjective data (what were the #’s, how did it feel, how repeatable was it, etc.) will help you find your ideal foot and hip position. Just don’t go too overboard with paralysis by analysis – if it’s comfortable, repeatable and elicits the best numbers, go with it.

Now take a look at some clips of me: turning my back foot slightly inwards in college was actually extremely helpful and I had an almost immediate velocity jump…but this is only possible for me because my structure allows my hips to work well in internally rotated positions.

#2: Considering dropping (or modifying) throwing drills that work counter to your natural structure.

Remember Athlete A, the guy with awful hip IR? We initially forced roll-ins on him, thinking that it would help him get better separation and improve his efficiency – they did for me, and many others, right? Wrong. We spent several months wondering why all of his numbers were down 3-5 mph until we realized that he had lost the hip ER, vertical shin and back leg drive strategy that had always made him successful. Now, he’s up to 97 in pre-season bullpens, not bad for a 5’11” guy with “tight” hips. If you find that a more externally rotated femur works for you, actively cue it and reinforce that in your drills.

Case in point: Ben Heller, a big leaguer who regularly tops triple digits, told me that his primary focus in some of his early drill work is to feel the rear hip holding external rotation as he moves forward. I can’t argue with that. If it works for you, over emphasize that piece of the delivery in all of your drill work to reinforce that pattern.

“If it works for you, over emphasize that piece of the delivery in your drill work to reinforce that pattern.”

#3 Change your approach to mobility work.

Now, I definitely believe that improving active hip rotation range of motion is important (and likely beneficial) as long as you actually have a tissue restriction. It has been shown that pitchers with reduced hip rotational range of motion put greater external rotation torque on their throwing elbow and have greater horizontal adduction during the follow through (finishing more cross body). But if you’re pushing to pain, a pinch, bone on bone contact or getting anything but a true stretch, you might be doing more harm than good. One athlete emailed me that he was getting an MRI on BOTH of his hips – when he had been healthy two days before (no joke I got the following email):

What did you do? I asked. Turns out he thought that forcing through a painful end range on his hip mobility work would help, and he had given himself impingement symptoms that lasted for about a week.

Closing thoughts

While there aren’t any absolutes with how you should position your rear leg during the throwing motion, this is what we’ve noticed with many of the athletes we coach, and may hopefully direct your own mechanical efforts in a productive direction. The biggest takeaway is that you probably shouldn’t don’t do strict roll-ins or other extremely internally rotated drills for athletes who can’t get into those positions.

If you haven’t already, check out our Youtube video on this topic, below. Make sure to subscribe there to get notified when we post new content!

If you have any questions, email us or reach out to me on twitter.

As always, thanks for reading!

Here’s to reaching your potential,

Ben

Athletes or coaches interested in remote one-on-one or team programming? Reach out via this application form.