by Ben Brewster

Efficient pitching mechanics combine and utilize multiple planes of motion. This isn’t a particularly controversial statement – but let’s break it down further.

There’s the linear/lateral phase of the throw – the drive or “flatbed truck” as Paul Nyman referred to it. This feeds into the rotational phase of the throw, which can be further divided into two parts: east-west rotation (pure transverse plane) and north-south rotation (combination of frontal /transverse plane). Randy Johnson is a classic example of this east-west rotation, while Andy Pettitte is a good example of north-south rotation.

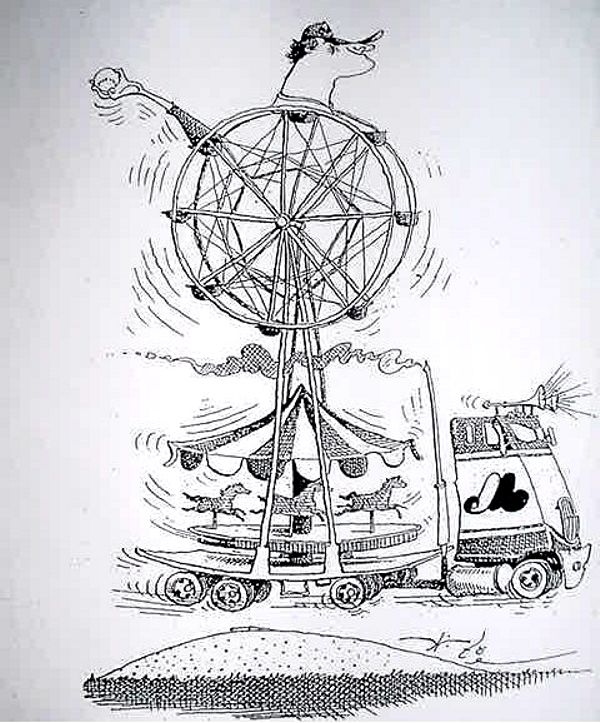

Nyman referred to the east-west component as the “merry-go-round” and the north-south component as the “ferris wheel.”

This is a useful, if somewhat comical, way to examine a high level delivery:

Very few elite throwers completely rely on only one of these pieces – as it’s being able to seamlessly stitch together this energy from all planes that allows a pitcher to create maximum ball velocities.

This concept is a big reason why a guy like Andrew Owen was able to experience such a velocity bump (from upper 80’s/low 90s to sitting 94-96 and getting signed by the Cardinals) – we took him from rotating purely in the transverse plane and added some “flatbed” (utilizing the rear leg drive more) and “ferris wheel” (adding some shoulder tilt) to his delivery.

What about the arm?

While this tri-planar concept is important, it isn’t enough, because it doesn’t take into account the arm. Maximum efficiency won’t be possible – even with a perfect flatbed truck, merry-go-round and ferris wheel – if the arm (and ball) don’t find their way into that plane of shoulder rotation from the start and stay there through ball release.

“Maximum efficiency won’t be possible if the arm (and ball) don’t find their way into the plane of shoulder rotation.”

Here are a couple images showing this happening properly, in two undersized 100+ mph hurlers.

The throwing elbow is in line with the rear shoulder when rotation begins, the arm lays back fully into this plane, and the shoulders/torso rotate around the spine. This visual from SETPRO, which I have posted frequently in the past, illustrates the plane, and shows the arm syncing into this plane during shoulder rotation:

Okay, this all makes sense in theory – but from a practical standpoint, what does it look like when the arm is out of plane?

Low Elbow / Arm Dragging

The arm can come out of plane at the beginning of shoulder rotation or at the end. When the arm is out of plane at the start of shoulder rotation, most of the time we’re going to be talking about a low elbow, also known as arm “drag” or “lag.” In biomechanical terms, the degree of shoulder abduction at landing should be 90 degrees (elbow in line with the shoulders).

With the arm lagging, shoulder rotation begins, but the arm is still way down below that plane. Here are two athletes showing this issue. Both were throwing 3-5 mph below what I would have “predicted” given their sizes, strength numbers, etc. This gives you an idea of how much of a problem this can be for velocity production:

Even if the arm catches back up 2 or 3 frames later (as it does in both of these pitchers), there was still a significant loss of energy transfer during the acceleration phase of the throw.

Flexion based / linear finish

This is the most common form of not keeping the arm in the plane of shoulder rotation, and it happens at the end of the throw. As shoulder rotation occurs, one of two things can happen. First, many lower level throwers cut off their rotation as they near ball release, forward flexing the trunk to finish the throw.

“Many lower level throwers cut off their rotation as they near ball release, forward flexing the trunk to finish the throw.”

This attempt to transfer rotational energy into a linear finish via the trunk is a major inefficiency, and one that can be blamed on the torso, not the arm. As the torso flexes forward (typically a well-intentioned attempt to “throw strikes” or get behind the ball), the arm also comes out of plane, finishing (pushing) straight down to the glove side hip, something I discussed here.

You can watch yours truly (back in high school), exhibiting this velocity killer. The black line is the angle of my shoulders, but rather than rotating in plane, I’m forward flexing into release.

Contrast this to rotating through your arm slot, in all three of these examples that I’ve talked about before:

The second outcome is that shoulder rotation actually continues, but the arm takes itself out of that rotational path to finish linearly towards the target. In this case, the torso is doing its job – but the arm is hijacking the rotation. This isn’t as big of a velocity killer as forward flexing the trunk (this HS pitcher below has still been up to 94 mph), but it’s still represents the arm not staying maximally synced in the rotational plane through ball release.

It’s worth noting that this particular pitcher does a lot right. This is about the only flaw I could pinpoint in his delivery. Speaking of which, look at that back foot position – the externally rotated foot/hip can really help guys maintain contact with the back leg if it works for their hip anatomy. But I digress.

For comparison, here’s an almost identical delivery, minus the rotational flaw at ball release. A 97 mph fastball from Brandon Morrow, ladies and gentlemen:

Regardless, of the culprit (torso or arm), the underlying cause of these symptoms tends to be the same: focusing on throwing strikes, not being wild, etc.

“The underlying cause of these symptoms tends to be the same: focusing on throwing strikes, not being wild, etc.”

This is fairly easy to notice if you look at the shoulder angle (contralateral tilt in biomechanical terms), corresponding arm slot (the two should match), and then follow those two angles through ball release. The arm slot should continue to follow through in the plane of shoulder rotation, not push down through the target, finishing on the opposite hip.

Note: the arm will eventually complete its natural deceleration arc and wind up near the opposite hip – that’s not my point. My point is that you can glean a lot of information based on where the arm goes in the several frames after ball release. Rotating properly will continue to send the arm on a deceleration path through the arm slot, ultimately ending up near the opposite hip.

Here’s a video demonstrating that distinction from Freeman Baseball, using Pedro Martinez.

So how do we fix it?

What’s interesting is that many of these athletes can rotate fine when you put them in a long toss situation or have them test plyos into a wall or baseballs into a net. It’s simply a context-based mechanical flaw.

While I don’t have a cure-all, here are some things to avoid that definitely can cause this issue to creep up.

#1: Over reliance on throwing strikes.

Pitching scared or trying to be “too fine” can lead to avoiding the rotational violence necessary to maximize the velocity side of the equation. Athletes should be in attack mode, not “I’m afraid to walk this batter” mode. As a coach, encourage that, don’t freak out and throw the clipboard every time a pitcher gets to a 2-0 count (yes, this actually happens). Even if the in-game pitcher doesn’t see it, the rest of the staff does, and that will be in the back of their minds the next time they’re in the game. Motivation to avoid failure vs. motivation to achieve success is relevant here.

I’m not saying for pitchers to yank the head, grunt, and throw the ball over the backstop every pitch. But there must be sufficient intensity (and the confidence to maintain that intensity) that the body doesn’t put the brakes on that rotation heading into release for fear (subconscious or otherwise) that they won’t be able to throw a strike.

“There must be sufficient intensity (and the confidence to maintain that intensity) that the body doesn’t put the brakes on that rotation heading into release for fear (subconscious or otherwise) that they won’t be able to throw a strike.”

Here’s Clayton Kershaw, on his mentality to throwing strikes. Counterintuitively, it’s not based on trying to throw strikes. The majority of the real-estate in his brain is focused on throwing the pitch as hard as he can, while the back of his mind understands the target he’s going for. This approach works for him because he has such a repeatable delivery, and he has ingrained his motion over thousands of reps. Getting to this point where your mechanics are second nature (aided by a strong pre-pitch routine) will allow pitchers to trust this approach to strike throwing.

Here are some questions to ask as a coach:

- Am I only having my guys practice or throw bullpens at sub game speeds? Why? Why not finish certain bullpens with 2-3 stand in hitters at game intensity?

- Am I only rewarding or cueing strike throwing? (i.e. keeping track of strike % only or punishing wild pitches or balls). Why not pick 85 or 90% of a pitcher’s max velocity and keep track of quality pitches above that selected velocity threshold?

- Do I have a plan for blending velocity work (long toss, pulldowns, WB testing) into command work, or am I expecting guys to go from throwing into a net at 100%, to throwing bullpens at 75%, to suddenly commanding at 100% in game situations?

#2: Long toss

Long toss is unique in that it encourages throws to be on-line, while also encouraging a high intensity, rotational finish to reach max distances. Immediate “command” feedback is there if the ball sails way off line, and it’s also there in the form of seeing how far the throw went (“velocity feedback”). In essence, you can work on the rotational aspect of the throw without sacrificing keeping the delivery on line (properly directing rotation and intent through the target).

“Long toss is unique in that it encourages throws to be on-line, while also encouraging a high intensity, rotational finish to reach max distances.”

Note: if you’re dealing with a low elbow guy, long tossing on an arc can make the problem worse. I’ve had success with low elbow guys focusing on getting the elbow up and driving balls down and on a line. They’ll still get the immediate feedback and benefits of long toss, even if they aren’t throwing to maximum distance.

#3: Patient torso rotation / let the arm climb

If an athlete finishes well, but has a low elbow/arm lag, one cue that can help is the cue of being patient with the torso rotation. In other words, let the arm spiral its way up before beginning to yank the torso through. I’ll use the spiral staircase analogy – rather than waiting until the arm is halfway up the staircase and dragging the elbow up through the ceiling (and then down the hallway), wait until the arm gets to the top of the staircase and drive down through the hallway.

Here’s what firing the arm up through the ceiling looks like:

He finally gets the arm in plane and then tries to redirect that force down the “hallway”:

Herrera lets the arm spiral up to the top of the staircase (elbow in line with the angle of the shoulders) before shoulder rotation begins, so everything is driving down and through the ball from the first instant of shoulder rotation.

This is a tough habit to break, so consider backing up into various constraint drills that cue the desired pattern – driving down through the ball and being patient with the torso rotation until the elbow climbs to shoulder height. Here’s that same athlete below:

#4: Find the disconnect

If an athlete can do it in certain drill-work or scenarios, but not in others, then you need to establish which variable creates the disconnect.

Can he rotate effectively and keep the arm in plane during the crow hop but not the delivery? Try long tossing out of the pitcher’s delivery to work on that.

Is it flat ground to the mound where the breakdown happens? Try blending long toss throws with mound throws and add in mound plyos.

Is it only when a batter steps in? Practice intent bullpens with stand-in hitters. Start at 57-58 feet and work back to standard distance from there once it becomes comfortable.

Is it only when a catcher sets up a small spot to hit and the coach is watching? Making too small of a target can mess with repeatability, especially if there is a motivation to avoid failure present. Try cueing throwing through the center of the catcher, rather than to the mitt, knee, or a specific quadrant of the strikezone. Always trying to blast the center of the catcher – regardless of where he sets up in the strikezone, can flip on that light switch in the brain and avoid the being too fine syndrome. Short bullpens from 57-58 feet can help too.

#5: Explain the issue

When the athlete understands the issue and knows what exactly they’re trying to achieve, it makes your job as a coach easier. Keep it simple. Let the arm climb to shoulder height before beginning rotation. Rotate violently – but direct that rotation through the target – and don’t ease off the gas pedal into release.

When in doubt, find a mechanical model specific to the athlete in question, and put up a side-by-side for them to see what you’re talking about. It will take the abstract and make it very, very concrete.

Closing Thoughts

We made a video that might help clarify things a bit further, so make sure to check it out below. Please share this post if you found it helpful and let me know your thoughts on twitter or at contact@treadathletics.com

Here’s to reaching your potential,

Ben Brewster

Athletes or coaches interested in remote one-on-one or team programming? Reach out via this application form.