One question I get repeatedly takes some form of the following:

My coach wants me to play summer ball, but my velocity and stuff isn’t anywhere near where it needs to be for me to play at the next level. Should I pitch or take the summer off to train? Or, should I try to train hard while also pitching?

—

A Conflict of Interest

At the heart of this problem is the conflict of interest between college coaches and many of their players – coaches need to win games to keep their jobs (and advance their careers), while players, at least at the higher levels of college baseball, often have the primary goal of playing professional baseball in some capacity.

For coaches, this means getting their players polished and ready to compete to the best of their ability with their current stuff. Throw more strikes, stay composed in pressure game situations and refine off-speed pitches. Occasionally, mechanical tweaks or pitch grips alone will lead to minor improvements in stuff (great!) but most of the time, pitching coaches scoff at players who express the primary desire to improve their raw stuff over other refinements because it’s not as direct of a path to wins.

For players, if playing professionally is the goal, most know that their raw stuff needs to improve, and that constant competition makes it harder to pursue velocity building programs and aggressive strength training or weight gain regimens. Don’t believe me? Try going to 5 games a week over the summer. This entails 3 to 6-hour bus rides each way (depending on the league), 5 to 6 hours at the field, while still trying to get good lifts in and hitting your nutrition numbers. Good luck! That being said, there still are times when playing summer ball makes sense, even if stuff development is a priority.

—

Scenario #1: Welcome to college

You’re a freshman in college and your stuff isn’t quite up to par yet. Maybe you redshirted or only got a few innings here and there. While you’re tempted to take the summer off to keep working on your strength and velocity gains, there is value in getting some innings under your belt one or two summers during college if you didn’t pop the college cherry during your spring season. For me, learning composure on the mound, gaining confidence that I could get hitters out at the college level, and getting live reps on my pitches was an important step, even if I was still far from where I needed to be stuff-wise. This isn’t to say that you must play summer ball, but taking 2-3 months when you weren’t able to get live reps in the spring helps from getting too far away from the game. Not to mention, summer ball is fun. The bus trips may be hell on your recovery, your host family might have an obnoxious set of house rules, and you may wish your training schedule was more regular – but those couple summers are some of the best memories I have.

Recommendation: could go either way.

Summer ball will develop other tools as well…like two-ball ability.

—

Scenario #2: Spring innings eater

If you threw 40+ innings in the spring, but your stuff is still 3-5+ mph from where you know you need to be to get next level interest, it makes little sense to play summer ball. Spend your effort developing your raw tools, and once you get there, work to refine them. Refined 88 mph pitchers don’t draw scouting interest, and the only 88 mph pitchers who you’ve seen in the big leagues (like Hendricks or Maddux) can or did throw 93 when they burst into the league, and earned the right to stay with below average velo by pure domination alone. Even Bartolo Colon (who now only throws in the 88-91 range), used to throw upper 90s when he was first in the league, so keep in mind that your stuff does have to be at least average for what guys at the next level have, otherwise you better have something else extraordinary (like throwing 88 from submarine, a ball that moves 2 feet, or 1 in 10,000 command like Maddux).

Recommendation: take the summer off to develop your stuff

—

Scenario #3: Unpolished prospect

Your fastball is within a couple of where it needs to be, but you’re working on refining your command, consistency or an off-speed pitch. You’ve been invited to pitch in the Cape Cod league or another highly competitive summer league. In this case, more live innings (assuming you weren’t abused in spring ball), is exactly what you need to keep working on refining the stuff that you already have. It’s still important to keep training and eating properly in-season, but the car has been built. Now, it’s time to learn how to drive it.

Recommendation: play ball.

—

Going Pro: are we selling a false dream?

A common criticism of the velocity training crowd is that we are just selling false dreams at achieving pro status, when a majority of those pursuing it, oftentimes against coaches wishes, won’t ever actualize this dream.

“Just take pride in being a good pitcher and getting hitters out at your current level and abilities. There is pride in being a good college pitcher and hanging up the spikes after 4 years.”

To that, I say three things.

1) There is absolutely pride in being a good pitcher. Nobody is forcing anyone to train his stuff, especially if that player has no desire to play at the next level (or doesn’t feel he has the capability of doing so). This is totally cool. I’ve played with some guys who accepted from the start of their four years that their careers would end, and they had fantastic college careers (more successful than mine ever was, despite getting drafted). This is admirable.

Here’s the flip side – coaches, I’m talking to you:

2) If a player has it in his heart that his goal is to get to the next level, no matter how far-fetched you think that goal, and you pressure him into settling, try to talk him out of working to improve his raw stuff, or tell him that he isn’t capable of making it any further in the game…

Fuck you.

Cut him or bench him if he’s not yet good enough to pitch for your team. Have a heart to heart with him if you truly believe he’s misguided..but don’t forcibly stand in the way of a kid’s goals because of what you think they should be.

3) Here’s the third reality: chasing rabidly after a dream that you actually care about, pushing through failure and clawing your way towards the limits of your abilities teaches an athlete far more about how to win at life than obediently stifling that dream and following orders. Dream big. Make mistakes. Learn from them. In the process you will learn far more about yourself than the athlete who was just “gifted” his abilities.

Call it corny (I guess it is), but it’s true.

—

Wrapping it up

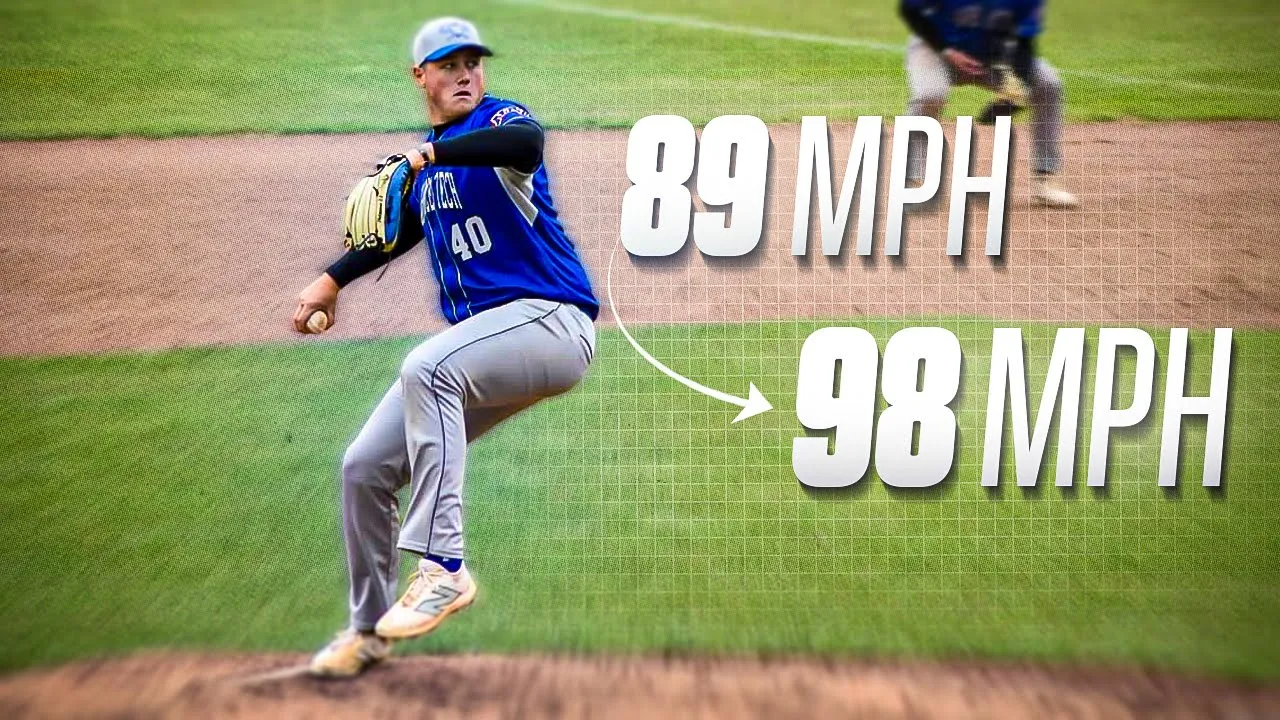

Playing summer ball can definitely be a good decision, but so can smart and hard training on an intelligently designed program. Most guys aren’t where they need to be as far as lean body mass or strength/power metrics. Many guys could stand to go through a structured weighted ball/long toss regimen rather than ride buses and eat Wendy’s all summer just to snag 22 innings pitched. Hell, my biggest jump in velo came between age 21 and 22, following the only summer of college that I took off from competing. Can summer ball be a good call? Sure, but you have to understand the context. It’s up to you to weigh the pros and cons of each in making your decision.

Check out my e-book Building the 95 MPH Body and learn to throw harder by clicking here!

Here’s to reaching your potential,

Ben