by Ben Brewster

This post goes hand in hand with this youtube video. Give it a watch after completing this article.

I will be honest, I didn’t have much of a clue how to use my lower half for just about all of high school and college. As a guy who was trying to learn hard-throwing mechanics from total scratch, it was too many moving parts, to where I just gave up and decided to throw from a slide step.

Life was better that way – I could just come set, pick my front foot up and put it right back down again. I didn’t have to worry about a leg lift throwing my timing off and yanking open my front side.

This worked – to a point. But only because I was tall enough, athletic enough and had an arm that moved well enough to do so.

I touched 87 this way in high school (whoop-dee-do), and touched 93 in college before ever learning I actually had this thing called a back leg.

I eventually learned how to use my glutes and hamstrings to propel myself forward and transfer that energy up the chain. This was largely by accident, as I described in this article – I was trying to imitate Fernando Rodney, who gave me hope that throwing 100 mph was possible from a slide step after seeing him do so in the world baseball classic. My long toss (which I performed out of my slide step rather than a crow hop) jumped up from 330 to 380 feet in one day.

Yes, I was using my glutes and hamstrings for the first time ever, but it was the positions I was getting into prior to the lateral drive that allowed me to actually tap into those muscles and transmit that energy laterally through my center of mass.

Rodney sat back into his heel, leaned into the target and then utilized his glute and hamstring to begin the drive. But that initial move started the weight shift – and that initial move, for me, was everything.

I didn’t overthink it beyond that for a few years. I did roll-ins to learn to separate my hips and shoulders, and I threw like Rodney from my slide-step. From then on I was mostly 90-93 touching 95, good enough to get drafted. After being released, some tweaks got this to consistently 94-95, still not where I would have liked it to be.

Maybe my genetics really were a limiting factor to how hard I could ever throw. Were all these teammates touching upper 90’s really that much more gifted athletes?

I refused to believe so, and decided to keep searching

Note: I’m not saying everyone can throw upper 90’s if they just try hard enough, but in my case I had most of the things that are hard to teach, like fast twitch ability, shoulder laxity, levers, etc. so I felt there was a good chance it was still possible I was underachieving relative to my potential.

The Breakthrough

The next breakthrough occurred in another odd experiment. I had been trying to rehab what I would soon learn was a partial UCL sprain. It had been lingering for several months and was not responsive to conservative therapy and rest. An MRI showed nothing wrong, as did a first stress ultrasound. In a stress ultrasound, the doctor applies a valgus force to the medial elbow while the technician has a live feed of the ligament on the screen so that a tear can be diagnosed if the ligament displaces more than it should.

I pointed out that the technician maybe applied 5 lbs of valgus force to my elbow during the first negative test – far less than in throwing a 90 mph fastball and not enough to recreate that sharp pain. I knew something was wrong with my elbow, so I requested a second diagnostic ultrasound test where they would apply enough pressure to replicate the sharp pain I felt while throwing.

Leading into the test, I was instructed to throw beforehand until I replicated the symptoms.

The slide-step, normally consistently 93+ on flat ground, was down around 88. Not surprising – my elbow was sharp and stabbing. That’s to be expected. After a few, I hopped on the mound to throw about 5 more. Healthy, my mound work would normally have been 1-2 mph harder than flat, but I hadn’t been on a mound in over a year.

I tossed a few: 90-91. Okay cool, so everything is down about 4-5 mph today. Not surprising. But then I decided to try something I had been toying over in my head – after watching this throw from Tim Lincecum, back when he was topping triple digits as the skinniest, most promising pitcher in the world.

It was the same thing I noticed in my own slide step – if I could get the weight shifted further away from the rubber before getting into and driving off my back leg, the upper half and arm snapped through quicker.

If I was about to need surgery or months of rehab, now was my chance to test it out for a few throws.

What I expected was 90, maybe 91 at best. It felt awkward as my first time trying it, and I was very obviously not synced up properly. Sharp pain shot through my arm with each throw.

94.6.

94.3

94.1

94.3

94.1

…

Where would those numbers be when I’m not down 4 miles per hour on everything else, first time on the mound in a year and throwing indoors through sharp shooting pain?

This is when I knew the “drift” – one of the keys to Tim Lincecum’s efficiency, could be a secret weapon.

I just had no idea how to harness or teach it.

“This is when I knew the ‘drift’ could be a secret weapon…I just had no idea how to harness it.”

Though I’m still working to find my way back into full health (I’ll save you the details – my elbow is fine now), I was sitting 96-98 in indoor bullpens after elbow surgery utilizing this “drift” – while the slide step stayed exactly where it should have been: 94-95.

So what is the drift? How do we teach it? What other big leaguers do it? Why does it work?

Let’s dive in to my current thoughts, in trying to explain this phenomenon.

What is the drift?

The drift is a term I coined to refer to the initial forward move that occurs during the leg lift – this is not an active drive, but a shifting of the center of mass forwards, away from the rubber, preceding the active drive phase of the back leg.

Despite being what the majority of high level throwers do to initiate forward motion, this is counter to what traditional pitching teaches with “balance points,” which focus on keeping the weight gathered over the pitching rubber during leg lift and prior to the linear move or drive off back leg.

Watch Nolan Ryan execute this move below:

Interestingly, this explains why Ryan said that he felt he threw harder when he lifted his leg higher – because the leg lift was his cue to move forwards, the higher he lifted it, the further he was able to get away from the rubber before sitting into the back leg.

Three reasons I believe this hasn’t been discussed much in the pitching realm.

#1: Most pitchers who drift, don’t realize they’re doing it. Oftentimes, they just try to be athletic and up tempo, and their bodies learned early on that shifting their weight during leg lift allowed them to throw harder. It’s also common that some pitchers throw harder from the windup, not realizing that it’s the forward move during leg lift that sets them up for better energy transfer later on in the throw.

#2: It’s easier to teach balance points. You can take a group of 12 year olds and work on an up-down-out lower half in a very systematic and repeatable way. Try to teach a 12 year old how to move dynamically through his leg lift – you’re going to have a hard time making much headway in all but the most athletic kids. Balance is easy – and to some extent, it might help create more repeatable mechanics in the majority of kids who are falling all over the place when they throw. But just because it lowers a 12 year old’s walk rate doesn’t mean it’s what the majority of the hardest throwers in the world do.

#3: It’s hard to see this weight shift from a rear view – you know, the only camera angle ever shown on live baseball broadcasts. Begin to pick apart side angles of your favorite big leaguers, and it tells a completely different story. Let’s take a look.

What are some examples of the drift?

There are two main “styles” of drift, as far as I can tell.

The coil and drift – this style incorporates a counter rotation to initiate that forward move. They hit their dynamic balance point 6-8 inches out front of the rubber. This is what worked best for me.

Bartolo Colon threw 100 back in the day. Watch how he uses this initial move to hit a dynamic position away from the rubber.

Roger Clemens touched upper 90’s, using a coiling mechanism to initiate movement towards the plate.

Aroldis Chapman moves forward as he lifts, setting up efficient lower half positions.

Tim Lincecum – back when he threw hard, shifted his weight the most aggressively, while keeping everything on time.

Bruce Rondon has consistently thrown over 100 mph – his dynamic balance point occurs out front of the rubber, allowing his center of mass to be rapidly accelerated laterally by the back leg.

The straight on target drift – this style doesn’t have any counter rotating, the pitchers just hit their peak leg lift out front of the rubber. They’re still hitting their dynamic balance point 6-8 inches out front, rather than stacked over the rubber.

Jacob Degrom has been up to triple digits as a starter.

Justin Verlander is obviously Justin Verlander. Over triple digits deep in games whenever he wants.

Carson Fulmer was up to 99 at Vanderbilt at 5’11”. His weight comes forward during the leg lift, only then does he stay back during his drive once the train starts moving.

Robert Stock has been upwards of 100 mph and made his underdog debut in 2018. Watch how he shifts forward during leg lift, hitting the drift.

Gerrit Cole (in high school, here), aggressively shifted his weight before applying the back leg to his center of mass – saving up this hip abduction until it could be used efficiently.

Aaron Sanchez, who appears to be “all arm” from rear view broadcasts, actually makes excellent use of the drift to shift his weight towards the target. While he doesn’t have much drive off the back leg, this shift helps utilize what drive he has.

I can’t tell what I’m looking for, help!

If you’re wondering how to be able to tell if a pitcher does the drift, after reading this article, ask yourself: would he be able to pause if you forced him to stop his delivery at peak leg lift? The answer should be no, he would fall on his face, because if he’s able to hold his peak leg lift it means the center of mass is still directly over the back foot.

What about slide steps or quick pitches?

Even if you don’t notice a heavy forward move, many pitchers maintain the “drift” even in their slide steps or abbreviated leg lifts by coming set wide so that their center of mass starts out front of the rubber. A lot of them also bias more of their weight towards the front foot so that when they lift the front leg they are already moving forwards. Once they hit that dynamic balance point, then they shift into “stay back” mode, where the head and upper half are held back over the rear hip once the train starts moving.

Foltynewicz (who tops out in the triple digits), demonstrating the drift in an abbreviated leg lift.

Roy Oswalt, coming set 60-40 on the front leg to encourage this drift / weight shift during a quick-pitch or abbreviated leg lift.

We can keep going down the list, but I’ll stop there.

What is the theoretical basis for the drift?

This is my best guess for why it seems to be effective. Just like linear momentum rasies potential ball velocity in a running pulldown (assuming you can transfer that to the ball), an increase in linear momentum in the pitching delivery would raise potential ball velocity as well.

How do you do this in an efficient way?

Trying to sit deep into your back leg without shifting your weight, and then lunging off your back side may work, but it’s very energy intensive. You also deal with the problem of much of that initial force being directed straight down into the ground, rather than directed more laterally into the pitching rubber.

The drift is a “free” movement that hardly costs any energy , and allows you to save that available hip/knee extension and hip abduction until the majority of it can be directed laterally into the ground (once the center of mass has actually shifted away from the rubber).

I liken this to standing directly next to someone and trying to knock them over with your hip, to standing 6-8 inches away from them and trying to knock them over with your hip – the increase in efficiency and force is substantial, so saving up your rear leg until all of that force can be directed where you want it is probably more effective than muscling your way down the mound.

“Saving up your rear leg until all of that force can be directed where you want is probably more effective than muscling your way down the mound”

Does the drift work for everyone?

In theory, yes.

Waiting to apply your back leg into the throw until the center of mass has shifted away from the rubber should give you more usable energy towards the target.

In practice, no.

Some pitchers have learned to time and sequence up their deliveries based upon this balance point position they were taught, and so trying to change the forward motion during leg lift can screw with the timing of everything else up the chain.

We had this issue with Andrew Owen, a pitcher that came to us at 90-92 mph and got to sitting 94-96 indoors before being signed by the Cardinals.

We actually tried, after the initial velo bump, to change his weight shift, and it led to a timing breakdown further up the chain and worse numbers. Rather than force through a change, we stuck to what was working and backed off, allowing his body to stick to what was eliciting the best results for him. This doesn’t mean the concept wouldn’t work in theory, but chasing it wasn’t worth it in this instance, especially given how close he was to the spring season and trying to get signed.

A rare example of an elite velo guy who doesn’t have much drift is Nathan Eovaldi. He comes to what is basically a balance point, then drops, drives and rotates. Before you claim that this totally disproves my theory, just realize that he’s:

- A giant.

- A strong, lean and fast twitch giant known for squatting 500 lbs for reps.

- A true max effort delivery.

- Has insanely efficient front side bracing, meaning that the massive amount of energy he does create on his own (using his strong legs, and probably some of it wasted), he captures almost all of it up the chain via efficient rotation.

This just goes to show why there are so few absolutes when it comes to pitching mechanics – even if the drift is worth miles per hour for most pitchers, it doesn’t make it an absolute necessity for throwing hard if other boxes are checked to overcome this one inefficiency, and that potential velocity might not be readily accessible unless you can still sequence the finish of the throw.

Are balance points completely useless?

If the goal is to maximize velocity, it’s clear that the vast majority of the hardest throwers in the world have a shift of their center of mass during leg lift. Some do this more aggressively than others, but the strictly interpreted up-down-out method is not the most efficient from a weight shift perspective.

Still, some MLBers exist who swear by balance points as far as repeating their deliveries, and although many of these guys don’t throw into the truly elite ranges (most of these guys are low 90’s, touching mid 90’s), who am I to argue with them? Not everybody needs to throw upper 90s to get to where they need to go, and I’m receptive to the fact that some pitchers probably are aided by a slower tempo and keeping their weight back during their leg lift.

Would this be my first choice to teach to an athlete who comes to me desperately needing to add velocity? No.

How do we teach/learn the drift?

Ah, now we’re talking. I’ll be the first to admit that I still don’t fully know how to reliably teach it. Some guys get it, others it can take a long time or sometimes never quite clicks. Part of the struggle is that it’s hard to practice and repeat at lower efforts – the body positions that the drift put you in really force you to drive very hard and yanks the upper half through in order to not fall on your face. As such, it’s not the easiest thing to work on with 30% effort dry reps.

A few cues/drills to try:

#1: “Lean into your leg lift”

This is one of my favorite cues for athletes who are working on the drift, because it lets them worry about keeping everything the same in their leg lift except one variable – a slight lean into the target! Everyone interprets this differently so if they’re screwing up the move, we’ll change cues.

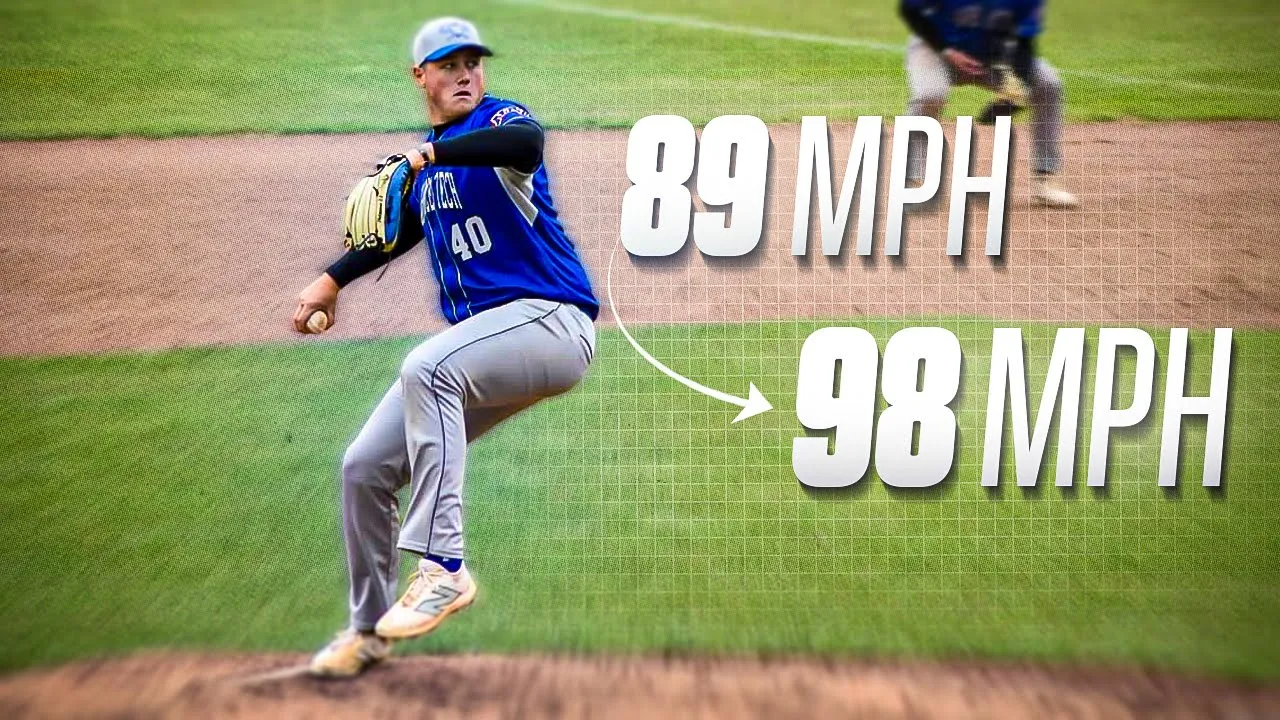

This is one of the main cues we used with my buddy Kyle – catch his before/after below:

Worth noting for Kyle, it took him about 6 weeks to feel comfortable with the move to where it represented such a significant bump in velocity as shown above.

#2: “Hit your balance point 6 inches away from the rubber”

I like this cue because it still helps create a repeatable, controlled feel to the leg lift (in other words, not an uncontrolled fall). It’s like you’re just hitting your balance point a bit further out front instead of right over the rubber. Justin Verlander is a perfect example of this – if you were to keep his delivery exactly the same but take away the drift, he wouldn’t throw nearly as hard or sustain that velocity as deep into game.

#3: “Stay inside your back foot during leg lift”

Another way of thinking about it, this can help guys learn to shift their weight, and is probably an under-appreciated reason why hooking the rubber may help certain guys as much as it does – it encourages the athlete’s center of mass to stay in front of the rubber during leg lift.

#4: Step-back drills

Understanding the concept is one thing, but actually being able to do it is another. We’ve found that just trying to do this move from one’s delivery can feel very flat-footed, so being dynamic is the best way to learn it. While walking wind-ups are a good tool once you begin to feel this move, a better option to learn it is step-back drills, which force the weight to stay out in front of the back foot.

This can feel a lot more dynamic and makes the move a million times easier to learn. As it gets comfortable, shorten the distance of the step back.

Closing thoughts

The “drift” is just one piece of the larger velocity equation – a commonality between most (but not all) of the hardest throwers in the world. My best estimate is that it might account for 2-5 potential miles per hour, but just like a running pulldown increases potential velocity, that is contingent upon being able to stay well timed and sequenced further up the kinetic chain. If the timing isn’t there, it may actual worsen your velocity slightly, so keep in mind this is probably best experimented with in your off-season throwing, using objective feedback like radar readings to reinforce your best reps.

I would liken the “drift” to icing on a cake in the grand scheme of building an efficient delivery – if you still can’t segment your hips and shoulders, get your arm on time, accelerate your arm without pushing and transfer energy efficiently through a braced front leg, adding more momentum is just going to create further breakdowns. Once these mechanical guard rails are in place, you likely have a better chance of benefiting from the adjustment.

You can watch the video that accompanies this article below!

If you have any questions, email us or reach out to me on twitter.

As always, thanks for reading!

Here’s to reaching your potential,

Ben

Athletes or coaches interested in remote one-on-one or team programming? Reach out via this application form.