by Nick Siegel

Today’s article comes to you from Nick Siegel. Nick’s pitching journey led him to playing college baseball, going from 78 to 92 mph. During his own journey, he encountered his own struggles with the “Yips,” and after finishing college while rehabbing from tommy john surgery, began to dig deeper into the research looking for answers to a problem that he – and many others – recognize is far more complicated than the “mental weakness” stigma associated with it. What drew me to publish this piece is that it’s not just geared at athletes with the Yips – Nick neatly ties these concepts into how regular pitchers and coaches can use this research to improve focus, repeatability and command. This article was originally published on his blog and you can follow him for future updates on his research. Also, feel free to reach out to Siegel via email at bugsyjagger@gmail.com.

Rick Ankiel, the pitcher in the St. Louis Cardinals Organization, was a phenom on the mound his rookie year, pitching a fall season in the big leagues by the age of 20. This all came to an abrupt end in the 2000 postseason. Ankiel not only couldn’t throw a strike — he couldn’t even throw the ball close to the catcher. He threw 5 wild pitches before being taken out by manager Tony La Russa. The next game was even worse. He threw 20 wild pitches in the first inning. Since that post-season appearance, Ankiel has never been able to regain his pitching ability and he had to transition to outfield to remain in baseball.

His problem? The Yips.

What are the Yips?

“The Yips” are a sudden inability to throw the ball accurately. Most view the cause of Ankiel’s as unexplainable. Despite many other players being inflicted in the 20 years since, little or nothing has been done to fix the yips in baseball. There still is no known effective treatment and little is understood about how they develop. Often a player inflicted will be stigmatized as mentally weak, ostracized by teammates who do not want to “catch” the yips, and most likely cut from the roster.

Much of the research done with Yips has been in individual sports such as golf, tennis, archery, and even dart throwing. What has been shown in research with yips-affected athletes is that there are clear neurological and physiological differences between a yipped-up athlete and the rest. Most players are left to the mercy of their coach to overcome the issue. Some are able to forget their experiences, but many still are never able to get the past failures out of their head.

“The research shows that there are clear neurological and physiological differences between an athlete with the yips and the rest.”

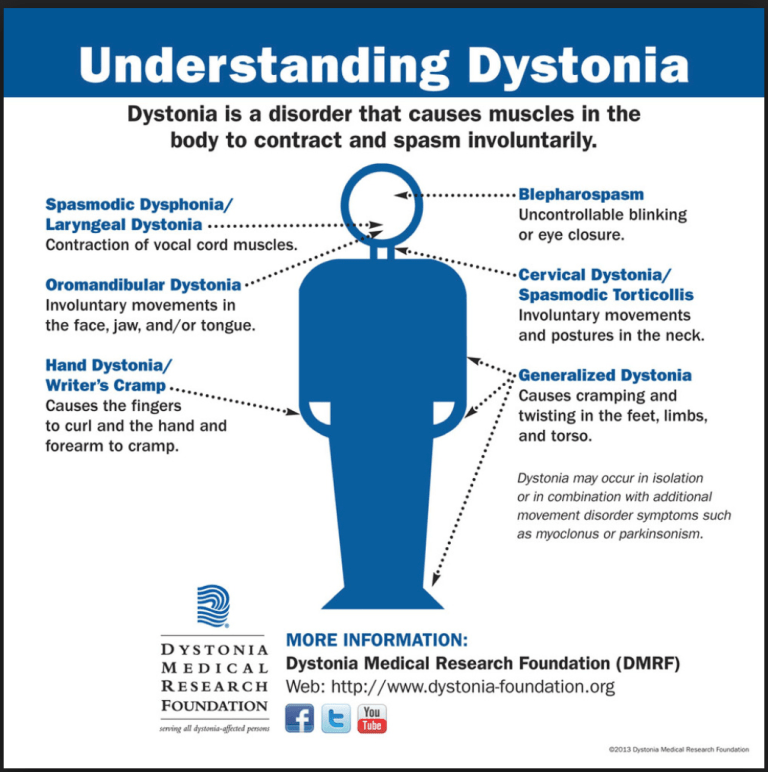

There is no consensus on the academic definition of the disorder (Pelz, 1989; Philippen & Lobinger, 2012; Smither , 2003). The yips were first described as an occupational cramp (Foster, 1977), that impacted professional golfers. Golf teachers defined the yips as a failsafe shutdown which surfaced following a decline of confidence that stemmed from unsound stroke golf mechanics (Pelz 1989). In the sport of golf, the yips were described as being a psycho-neuromuscular impediment affecting the execution of the putting stroke (Smith, 2003). Philippen and Lobinger also defined the yips as an involuntary muscle contraction that manifests itself differently across sports. From golfers to darts, the yips often involve interruptions of the executions of movements (jerk, tremor, freezing) of the sport specific limb(s). Of course this is accompanied by anxiety. So without question there are psychological, neurological, and physiological components associated with the yips (Clarke, 2015).

My definition of the yips, after review of the literature, is that they are a form of task specific focal dystonia that is heightened by anxiety. Focal dystonia is a condition in which certain muscles that have long been used repeatedly to perform a task, suddenly cannot perform that task anymore. It manifests itself with a loss of awareness of body position and locking of limbs. The “locking of the hand” feeling that many players report is caused by the muscles in the wrist activating at the wrong time. Because pitching requires hours of practice to fine-tune the exact moment in which the delivery must sequence, any disruption will interfere with strike-throwing ability.

Is there a scientific explanation for the Yips?

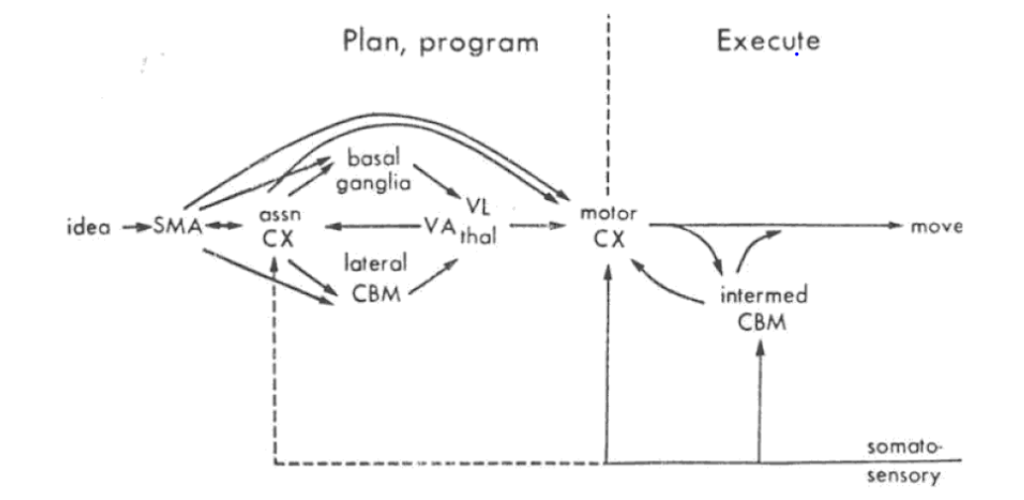

Dystonia disrupts the nervous system’s ability to allow the brain and the muscles to communicate and control movements. The types of complex movements in sports involve many areas of the brain and the area believed to be most affected by dystonia is called the basal ganglia.

Primary culprit: The Basal Ganglia

According to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), dystonia is considered to involve a breakdown of the basal ganglia’s function. The basal ganglia’s purpose is to control and regulate activities of the motor system so voluntary actions can be performed smoothly.

The structures of the basal ganglia in the hindbrain are also involved in the modification and learning of movements. These structures act indirectly on motor output, via its connection with the thalamus to widespread areas of the cerebral cortex. (Berkowitz, 2012) As such, the basal-thalamus connection plays a major role in learning movements and developing proprioception (body awareness, control and coordination) in tasks such as hitting a golf ball or throwing a baseball.

“The basal-thalamus connection plays a major role in learning movements and developing proprioception in tasks such as throwing a baseball.”

Since the yips are heavily linked to dystonia (more on the different classifications of yips in a bit), and dystonia is believed to be a deterioration of the basal ganglia, it is fair to use what is agreed upon by NINDS as credible evidence that the breakdown of the basal ganglia function is a possible cause of the yips and that the yips are environmentally sensitive.

It’s probable that this is what happened to Chuck Knoblauch, another famous case of the Yips:

Examining how this deterioration occurs and the structures inside the brain that are involved in the proprioception of throwing will lead to further theories of how to apply the research of the dystonia continuum into a program to improve the yips in baseball.I

Secondary Culprit: Dopamine

So how does this breakdown of the basal-thalamus pathway occur? It’s thought to be linked to dopamine. Dopamine is the key neurotransmitter involved in this connection, and is directed from the basal ganglia to the thalamus. Neurotransmitters are chemicals that help cells in the brain communicate with each other. If dopamine is not sent through this channel, the basal ganglia breaks down, which results in the inability to carry out precise movements that rely on finely timed muscle contraction, relaxation and coordination, like throwing a baseball.

“If dopamine is not sent through this channel, the basal ganglia breaks down, which results in the inability to carry out precise movements that rely on finely timed muscle contraction, relaxation and coordination.”

Dopamine & Motivation

There is a limbic sector of the basal ganglia which plays a central role in reward learning using dopamine. Extracellular dopamine in the BG is linked to motivational states in rodents with high levels being linked to satiated “euphoria,” and low levels with aversion (Ikemoto, 2015). The euphoria feeling immediately sounded to me like when a pitcher is in the “zone”, where throwing strikes comes easy.

In humans, it was shown that low dopamine correlates to avoidance behavior, especially among the extreme perfectionist population. (Flett & Hewitt, 2008). This corresponds to the feeling of not wanting to be on the mound, something that almost all pitchers with the yips experience (we’ll get into the perfectionist piece later on). On the flip side, high amounts of dopamine produce higher motivational states, and low aversion (Ikemoto, 2015). To put it into baseball terms, when you focus on the reward of a strike, and block out negative stimuli (like the fear or consequence of throwing a ball), a pitcher will theoretically produce more dopamine, which will not only improve motivation for practicing (creating a positive feedback loop), but also aid the basal-thalamus pathway in the brain which plays a key role in carrying out complex movements with precision.

Do elite athletes have higher dopamine?

One study, done by researchers at the University of Parma in Italy collected DNA of 50 world class athletes. The research further shows the importance of dopamine in athletic performance. The study showed a clear positive association between dopamine transporters and top athletes. All 50 athletes tested had top scores in World/European championships and Olympic Games in sports such as basketball, tennis, baseball, canoeing, etc. The study found that the dopamine active transporter, or DAT, and its two variants (DAT genotype 9/9 and allele 9) is more prevalent in elite athletes compared to a control group.

The genotype 9/9 was five times more prevalent in the elite group occurring in 24% of the elite compared to 5% in the controls. Furthermore, allele 9 was almost twice as likely in top athletes than controls, present in 51% versus 30% of subjects (Filonzi., 2015).

“What this study suggested is a strong role of dopamine in high performance athletes.”

What this suggested is a strong role of the neurotransmitter dopamine in high performance athletes. This further highlights the importance of emotional control and psychological management to reach high-levels of performance.

How does dopamine influence brain function in expert vs novice athletes?

One study looked at motor planning during the pre-shot routine of expert golfers and compared it to novice golfers. In expert golfers, increased activation was found in superior parietal cortex, lateral dorsal premotor cortex, and occipital lobes while the novice’s brains showed more activity in the posterior cingulate, the amygdala-forebrain complex, and the basal ganglia. More overall activity also was found in the brains of the novices than the experts. Solely on the basis of activation of the limbic and basal ganglia regions it was possible for a blind investigator to correctly identify 6/6 expert golfers and 7/7 for novice participants.

“[In golfers] more overall activity was found in the brains of the novices than the experts.”

In the study, the novice who had the most inexperience did not activate the limbic regions but exhibited the greatest activation of the basal ganglia. This relates to dopamine because low amounts of dopamine will cause a malfunctioning basal ganglia to overwork.

An over-active basal ganglia tries to produce more dopamine thus disrupting the basal-thalamus pathway and becoming more highly sensitive to feedback given from the sensorimotor area. The muscles require precise timing during the delivery and muscle inhibition is the basal ganglia’s function. When disrupted, the involuntary movements of the yips can manifest.

Look at the difference from this study in brain activity. The top row (a and c) is a novice, and the bottom row is an expert. The expert has much lower basal ganglia activity (and total brain activity in general):

All of this suggests to me that the novice is too emotionally involved with their result and also cannot organize themselves to repeat any success he may or may not have. Milton also noted that only the novice golfers would ask questions concerning factors such as whether the distance given to each of the holes was similar, and if there was wind or not (despite being told beforehand to assume there was none). Milton thus concludes that novices were actively participating in the task, but were unnecessarily preoccupied with details that were irrelevant for the required task. Hence the reason efficiency in the mind of an athlete is so important is to filter all the unnecessary stimuli and focus on the task.

The Different Classifications of Yips

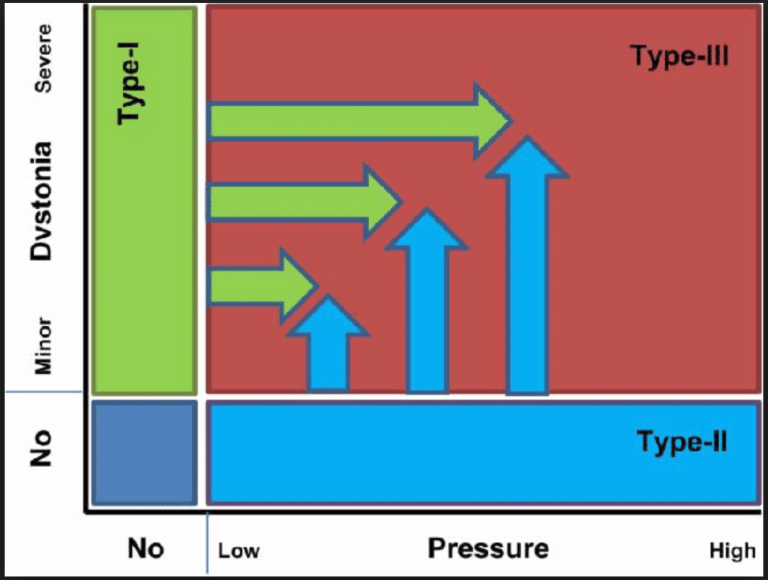

Two distinct types of yips have been proposed and both are thought to lie on separate ends of a continuum (Smith , 2003; Stinear , 2006) — Type I and Type II.

Type I Yips

Type I Yips (sometimes referred to as Lost Movement Syndrome or LMS) has been documented in research that suggests that the yips are instigated by a focal-dystonia, which is exacerbated by anxiety (McDaniel., 1989; Adler, 2005; Smith, 2000). However the precise etiology of FD is unknown. Reported dystonia-affected sports other than golf include table tennis (Le Floch, 2010) pistol shooting (Sitburana, 2008) and tennis (Mayer., 1999). Each of the respective sports reported limb or hand dystonia symptoms. Type I yips are also associated with higher intensities of practice, concentration, tension, and years of competition.

Type II Yips

Type II yips are considered to be a form of psychologically based choking (Smith, 03). Type II yips are thought to manifest in disrupted attention as a result of increased self focus or distraction (Beilock & Gray, 2007). Interestingly enough while the yips have been known to lead to performance anxiety, there has been no difference noted between the anxiety level of golfers with or without yips during performance (Torres-Russotto, 2008). This type of yips seems to be related to the individual, as Type II yips is more likely to occur around the ages of 18-20 which is also when generalized anxiety starts to manifest itself in a person.

This increase in self-focus could be because of the environment the athlete is in or no clear cause at all. Either way, internal rather than external focus is the main aspect of type II yips, rather than an absolute breakdown of the function of the basal ganglia. This likely can be alleviated by turning the focus and attention of the athlete from an internal focus to an external one.

Anecdotally, one minor leaguer that had a promising career derailed by the yips explained the difference to me between his internally focused mentality and his friend who is a successful MLB pitcher. He said he was constantly worried about throwing balls and if he would get demoted, while his friend has a “don’t give a #$% mentality” about him that allows him to maintain a “see spot, hit spot” robotic thinking that prevents any yips from developing. “If he overthrows you and the ball rolls 100 yards down a turf football field, he won’t care that you have to run back to get it.”

Testing the Yips Continuum Model

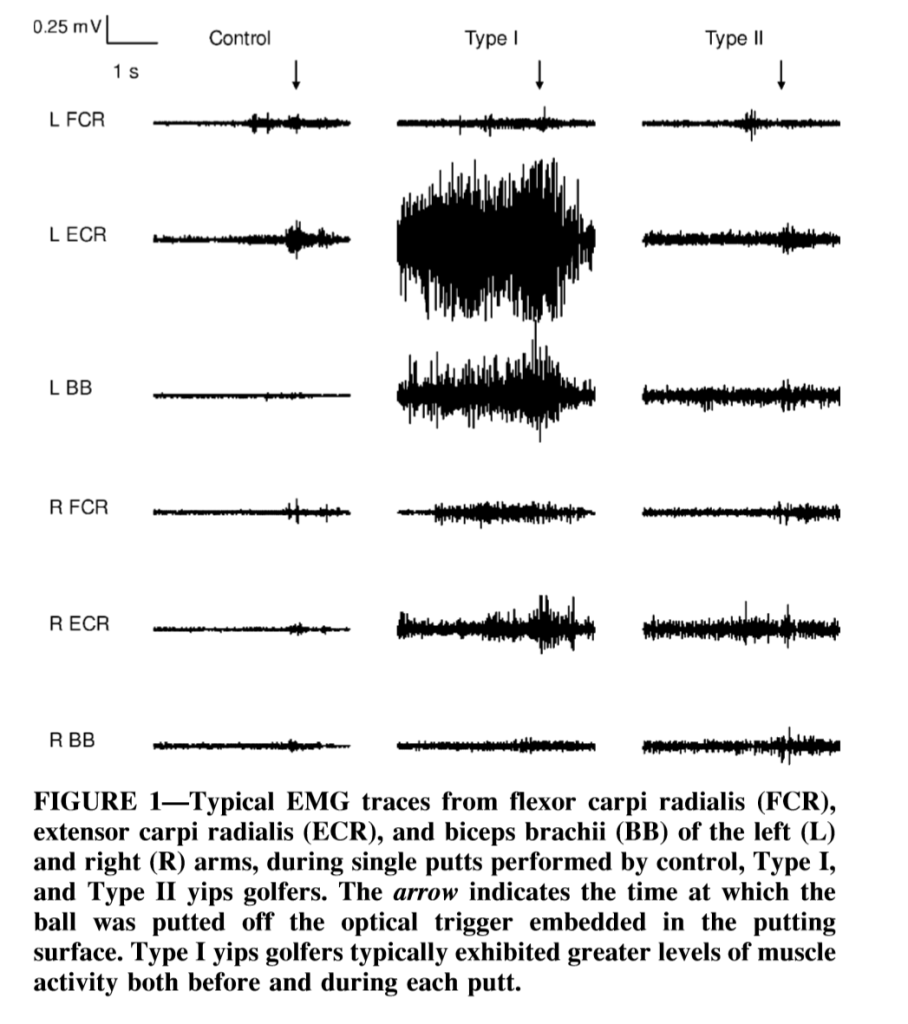

Following Smith, Stinear (2006) attempted to test the continuum model by employing behavioral (inhibition task), physical (EMG measurements), and psychological (state anxiety scores) measurements to compare groups of non-affected golfers and golfers that were either categorized as Type I or Type II yips.

Stinear hypothesized that the Type I group would show greater muscle activity while putting and more errors on a behavioral inhibition task than the Type II group and non-affected group. Stinear believed this was because patients with FD have shown impaired inhibitory function on several levels of the central nervous system (Torres-Russotto, 2008) and on behavioral responses which results in higher muscle activity and more errors on a behavioral response inhibition task than in control groups.

In addition, because of the strong association between “choking” and performance anxiety, the authors expected the Type II yips group to show generally higher cognitive state anxiety levels and worse performance under the high-pressure situation as compared to the Type I and control groups. Finally it was expected that once the chance to earn a monetary reward was removed all groups would improve their putting performance.

Results

The results only partially supported the hypotheses. The Type I Group exhibited higher peak muscle activity in the left arm as well as more errors on the inhibition task, as opposed to the non-affected group. There were, however, no differences between the Type I and Type II groups in muscle activity or error scores. In addition, contrary to the predictions, the Type II yips group did not differ in the general level of cognitive state anxiety. Furthermore, the high-pressure condition did not affect the outcome of the Type II group. Yet, when the chance to earn a monetary reward was removed, only the Type II group and the non-affected group improved their outcome score.

Measured (EMG) muscle activity during performance for Type I (Dystonia) group, while the Type II (associated with anxiety)group did not show muscle activity, but still had the yips. Exemplifies yips being on spectrum, ranging from dystonia to anxiety.

(Stinear, 2006) concluded that their study provided evidence for the model of two different types of yips. The golfers who experienced yips could indeed be categorized according to whether they reported mainly movement-related symptoms (Type I) or anxiety-related symptoms (Type II).

“The golfers who experienced yips could indeed be categorized according to whether they reported mainly movement-related symptoms (Type I) or anxiety-related symptoms (Type II).”

Based in part on these findings, one follow-up study proposed that symptoms which fell in the middle of the continuum, containing both dystonia-related and pressure-related factors, be classified as Type-III yips.

Do we really know what causes an athlete to catch the Yips?

In contrast to what was hypothesized, the results of Stinear (2006) also show that there were no differences between the Type I and Type II groups on a number of measurements. Thus, although it is certainly possible that the two types of yips are caused by different underlying mechanisms, it remains unconfirmed whether the Type I yips are caused by focal dystonia and the Type II yips by choking, as proposed. Despite the potential usefulness of categorizing the yips into different types, there is no validated procedure to do so at this point.

The environmental role in dystonia/Yips

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders (NINDS) has separated dystonia causes into three groups; idiopathic, genetic, and acquired. Genetic causes are interesting but self-explanatory and idiopathic dystonia refers to dystonias without a clear cause, which is what most dystonias are. The third, which is acquired, is from environmental or other damage to the brain, or exposure to medications.

This highlights the importance that an environment can have on a pitcher. While many yips-afflicted pitchers will have idiopathic causes where no clear reason is determined, I would theorize that many amateur cases of the yips are exacerbated (if not directly caused) by the environment the player is in.

“While many yips-afflicted pitchers will have idiopathic causes where no clear reason is determined, I would theorize that many amateur cases of the yips are exacerbated (if not directly caused) by the environment the player is in.”

This does not mean the team is the direct cause, as it is possible the athlete is disrupted by something else going on in his life.

Trauma

The development of anxiety-based disorders have been linked to history of traumatic experience, with the occurrence of a further traumatic event at a later time triggering the associated symptoms (Dohrenwend , 2013). For example, Rotheram (2007) demonstrated a relationship between Type I yips and a history of traumatic life-events, often experienced years before onset of the yips symptoms. Individuals exposed to trauma and prolonged stress can sometimes suffer adverse effects years after the event (Christianson & Marren, 2008; Forbes, 2007). Roberts, (2013) proposed that self-consciousness might be a characteristic of the yips, and suggested that performance breakdowns caused yips affected golfers to reinvest more conscious effort over performance, effectively causing repeated yips experiences. In my anecdotal but observed experience with players afflicted with the yips, it seems that one very bad outing can stick in a player’s mind longer than it should, creating a vicious cycle. Whether or not an athlete has the ability to shake off the experience could be rooted in their individual personality type.

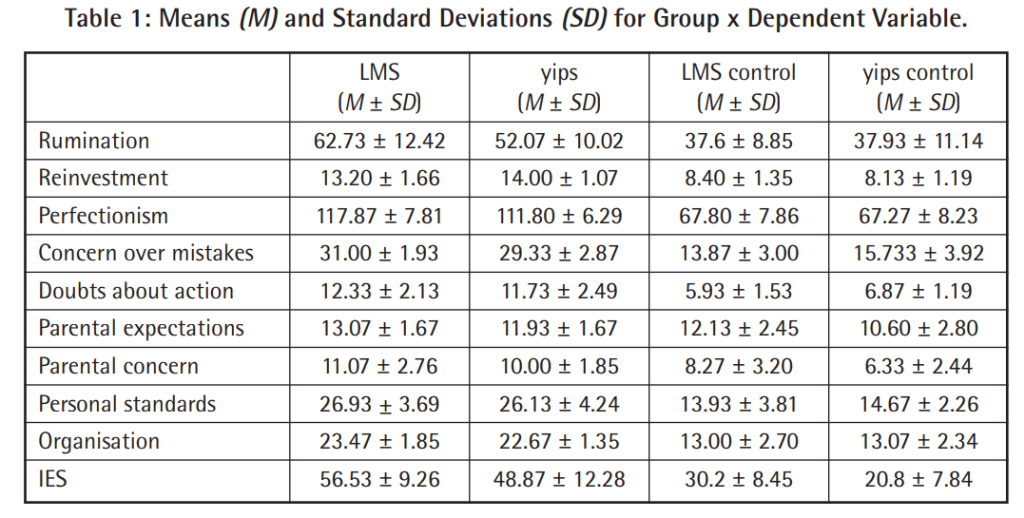

Personality Characteristics of Athletes with the Yips

What might cause an athlete to feel anxiety or fear toward a movement they’ve been doing their whole life? Research to date suggests that certain personality characteristics might increase susceptibility (Taylor, 2014). Perfectionism, for example, is considered to be a consistent predictor of anxiety across a range of populations (Frost & Henderson, 1991; Hall,1998). It has also been predicted that individuals with perfectionistic tendencies experience higher levels of anxiety following a perceived setback or mistake, due to an internal need for achievement. Consequently, perfectionism has received widespread attention throughout both sport and non-sport psychology literature (Flett, 2008; Frost, 2002; Stoeber & Otto, 2006).

“Individuals with perfectionistic tendencies experience higher levels of anxiety following a perceived setback or mistake.”

Stoeber and Otto (2006) also noted healthy and unhealthy profiles of perfectionism. The unhealthy involve high levels of both perfectionistic striving and perfectionistic concern, consequently increasing vulnerability to performance breakdown. Stoeber and Otto extended their findings off The Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMPS; Frost , 1990). The FMPS model still remains the most widely accepted model of perfectionism in sports. Together, perfectionistic striving and perfectionistic concern often reveal high correlations with negative outcomes such as depression, neuroticism, maladaptive coping, and negative affect (Stoeber & Otto, 2006).

Several studies have also reported that individuals affected by Type I yips invest considerable time and cognitive resources engaging in obsessive thinking about the experience, specifically focusing on the negative outcomes and potential causes (Bawden, 2001; Rotheram, 2007).

“Individuals affected by Type I yips invest considerable time engaging in obsessive thinking about the experience, specifically focusing on the negative outcomes and potential causes.”

Recent research has demonstrated that individuals experiencing Type I yips / LMS obsess over the problem in a highly self-critical manner. Furthermore, they also appear to display high-levels of self-focused awareness, specifically attending to physical sensations, thoughts, and emotions associated with the affected skill (Bennett, 2016). Research has also reported links between focal dystonia and self-conscious reinvestment (Grattan, 2001).

Despite perfectionism having both positive and negative components, perfectionism, coupled with self-criticism, is seen as maladaptive for sports performers, with negative self-defeating outcomes on behavior such as depression, body image dissatisfaction, and avoidance behavior reported among extreme perfectionists (Flett & Hewitt, 2008). Given the major factors associated with Type I yips / LMS (e.g. anxiety, intrusive negative thoughts, obsessive thinking), it can be assumed unhealthy perfectionism might well be an antecedent of these problems and could also exacerbate responses to both. Specifically, perfectionism might cause individuals to negatively appraise an experience of yips, doubt their ability, and invest increased conscious effort to regain control over the movement. In turn disrupting the automaticity with which the movement was originally executed.

The Vicious Cycle of the Yips

Is Elite Command a Result of Elite Focus?

Not exactly. This is why telling a player to fine focus and lock eyes with a small piece of the strikezone or catcher doesn’t help command for many pitchers. Evidence shows a difference between novices and experts in precision is not per se related to an ability like concentration (Doppelmayr, 2008).

Another way to think about it is shown by a riflemen study that took EEG data while shooting repeatedly at a target. The study discussed that novices focus their attention on the target for significantly more time before a shot, whereas experts use a more precise timing of focus only increasing their attention to the target at the last possible moment before trigger pull (Doppelmayr, 2008). The experts in Doppelmayr’s study relate to this gif, as you notice, Greg Maddux, known for his elite control, does not stare down the catchers mitt the whole time before and during his delivery.

If you’ve made it this far, let’s enjoy a few more moments of Maddux’s greatness:

[Editor’s note: this doesn’t necessarily mean that elite command doesn’t involve elite repeatability and movement pattern precision, or that elite athletes aren’t paying attention to what they’re doing – just that fine focusing and straining one’s attention intently on a specific target is probably not the overarching solution to ingraining highly repeatable mechanics]

Another elite command pitcher, Clayton Kershaw, discussing his approach to throwing the ball where he wants. Clayton is a guy who appears to keep his eye on the target (most pitches), so it’s interesting that he still doesn’t obsess or fine focus on the exact spot – but rather trusts the repeatability of his patterns and tries to throw as hard as he can within those patterns.

So if it’s not from focusing harder on where they want to throw the ball, where does that repeatability come from?

I would argue it comes from tens of thousands of well intentioned repetitions (Malcolm Gladwell and other researchers refer to this as “deliberate practice”), which ingrain the motor patterns, as well as sufficient experience in the competitive environment to be able to trust and perform these automatic patterns even under pressure and stress. Although no motor pattern will ever be exactly identical to a previous pattern (Bernstein’s Degrees of Freedom Problem states that “movement kinematics are not identical even when performing the same motion repeatedly; natural variation in position, velocity, and acceleration of the limb occur even during seemingly identical movements”), the error margin can still be reduced through meticulous practice.

Profile of the Athletic Brain

One study, (Kim 2008) examined mental rehearsals in elite vs. rookie archers. Rookie and elite archers were asked to mentally rehearse their performances while inside a functional magnetic resonance machine (MRI). What was found was that the brains of the elite archers were more efficient, meaning that less of the elite archers’ brains were active at a single moment in time compared with the rookie archers. Novice archers were predominately active in the frontal cortex, which contains the prefrontal cortex and is responsible for regulating emotions. The experts did not show any activity in the frontal lobe. The frontal cortex stands out and shows why the experts in the experiment, with advanced experience, long-term practice, coordination, and emotional regulation results in less cortical activity when challenged with task demands. This further supports the assertion that anxiety and a critical internal focus only make the yips worse. It would likely take 10,000 more shots before the brains of the rookie archers behaved more like the elite (Brager, 2015).

Here is a helpful graphic illustrating the process of skill acquisition from novice to expert – from unconscious incompetence to ultimately performing the skill automatically with a high degree of repeatability (unconscious competence):

Michael Jordan demonstrating unconscious competence – tens of thousands of repetitions make certain movements automatic with a high degree of precision.

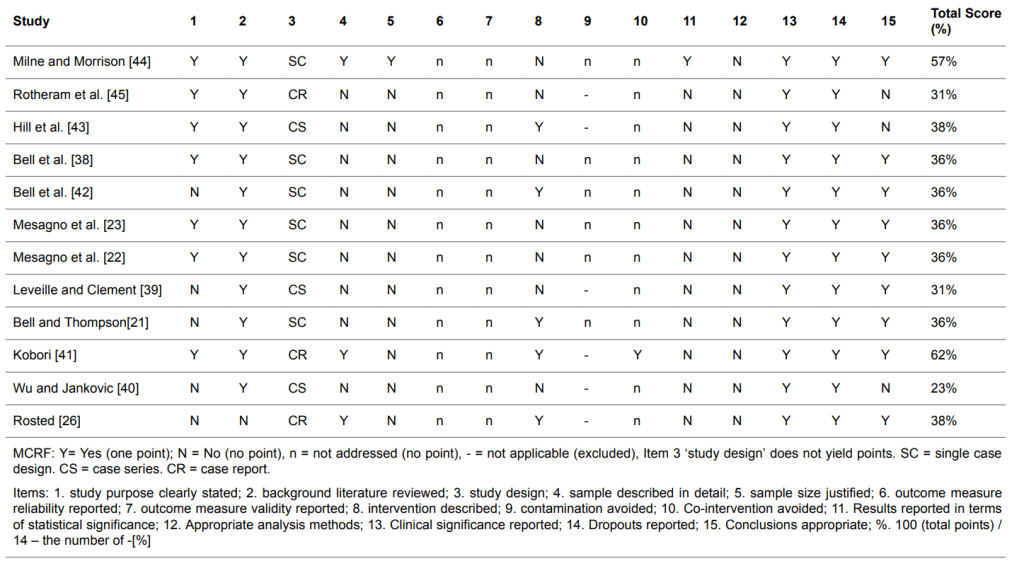

Is there a cure for the Yips?

Another noted aspect of yips studies is that the methodological quality evaluated on the The McMaster Critical Review Form found when a systematic review on the yips was done, there was almost no formal evidence to support that there are effective interventions for the yips (Mine & Ono, 2018). As shown in graph below:

Unfortunately, not many treatments for the yips have worked. To date, no single systematic review has been produced with regard to effective management for the yips in baseball. Many remedies for the yips that focus specifically on coordination of self thoughts including the usual meditation and “mind clearing” mental rehearsals. One study done with golfers by Domna Banakou of the University of Barcelona Spain (Banakou, 2010) suggested that to make the ‘dream’ a reality players mentally create a golf avatar of themselves with great putting ability.

Another suggested solution to the yips has been the use of botulinum toxin, similar to botox injections for wrinkles. Botox has been shown to help certain golfers with a physical disorder such as task-specific dystonia to remedy the co-contractions (Adler, 2005). This research may be good for golfers, but is unlikely to apply to baseball players as it has been shown botox treatments weaken the surrounding muscles, despite remedying erratic inhibition of muscles. Golf putting relies less on strength and power and more on a controlled repeatable movement. Throwing a baseball however does rely on strength and power not only to project the ball at a high velocity, but to also protect the ligaments in the arm. A baseball player would not be able to use this as a long term treatment, as the forearm and shoulder muscles play too major of a role in injury prevention and performance.

Rick Ankiel had a short term fix of his own: Vodka. He was quoted in an interview recounting the story:

Australian Kicker Precision Ball

To crossover to another professional sport and examine how they improve proprioception. Practice ball is made to give immediate, external feedback and keep athlete from maladaptive internal thoughts.

Despite lackluster research on yips treatments to date, an Australian Football League kicking program addressed a professional team sport that relies on the accuracy of accurate kicks. Accuracy kicking is one of the most challenging skills to learn. Even the most elite professionals only hit their targets 80% of the time. The complexity and specification for kicking in the AFL draws similar comparisons to throwing a baseball, as both are power dominated sports that require incredible amounts of proprioception.

Mark Williams brainstormed a new type of football and protocol to develop accurate kicks, with the backing of Sherrin, official ball maker of the AFL. The program is called the Sherrin Precision concept and it relies on both physical cues and mental cues to develop the accuracy needed. The ball physically differs slightly from the typical AFL ball as it has a larger sweet spot on each side of the ball, and is marked with a yellow line down the through the middle to give the player feedback on the spin line of their kicks.

The program brings the athlete through a progression of phases starting with basic kicking and developing into more complex tasks as each athlete completes the subsequent phase. While not studied or published in an academic journal, this program seems to be worthy of further investigation to see what can be extracted for a baseball pitcher.

The program works with helping elite players develop accuracy by relying on immediate feedback with the spin line, as well as mental feedback. Beginner advice includes feedback like making the ball rotate as much as possible, an external cue. Elite level kicking has more specific instructions for developing a player’s feel that relies more on specific external cues such as hitting the ball on a particular spot on the foot. Interestingly, I have seen coaches (Ben with Tread is one of them) use similar techniques by drawing a spin line on baseballs with a sharpie. This build in external feedback to the throw, with the goal on fastballs to create a tight black line indicating true backspin during the flight path of the ball.

What struck me as most interesting was that the coaching phases and styles taught on here feed back to my own theories on how accuracy is developed. Much of the program furthers my conclusions that external cues help a player more so than internal cues. This is not to say mental coaching and internal cues have no place, but it likely shouldn’t be the main priority for players looking to develop accuracy or overcome the Yips.

Final thoughts: Coaches

Research about the yips can be used to improve a team’s entire pitching staff rather than just one individual. If you understand what makes a yipped player, you may be able to apply a few key principles towards improving command of the entire staff. The yips are acquired and are environmentally dependent. One environment that produces the yips is one where a player is not looking forward to practicing (Ikemoto, ’15). Conversely, extracellular dopamine is linked to higher levels of performance, and a feeling of euphoria. Dopamine plays a large role in learning successful proprioceptive activities, Olympic athletes have been found to be more likely to have higher dopamine receptors than control groups of non-athletes (Filonzi, ’15).

Dopamine makes physical movement rewarding. Dopamine receptors are malleable and can be reshaped through physical movement. Dopamine is not the be all and end all when it comes to performance, but it plays a large role in the learning of movement. An athlete has to organize his brain to the task at hand and come up with a mental strategy of how to do it repeatedly.

Dealing with a gifted, highly driven athlete who demands perfection can be a double-edged sword for a coach. It is possible the player experiencing negative and self critical thoughts can be helped by a coach who understands this athlete. I believe a highly critical and negative environment focusing on the consequences of throwing balls or wild pitches is counterproductive to developing command or relieving the yips. To be clear, this doesn’t just mean giving pitchers unlimited in game chances. Instead, explain the possible issues and ways to eliminate these negative thoughts, if that is the case for the athlete. Although this will not apply to every yipped up player, it can help a certain subgroup of yipped up players.

From the Milton study, we know that while novices were just as focused on the task at hand as the expert golfers, the novices could not filter unnecessary stimuli and became preoccupied with details irrelevant hitting a golf ball. To further elaborate, a coach does not need to tell the player to focus on throwing strikes more, just helping the pitcher filter the unnecessary stimuli will actually lead to better results. For the golfers the unnecessary stimuli was asking questions like if there was wind, and how far away the hole was. For a pitcher it could be something like focusing on the last pitch, knowing someone is watching them in the crowd, or just being intimidated by the hitter thus throwing off the focus from executing the pitch.

Command needs to be taught the same way discipline and habits are taught. Think of command as a habit gained through consistent daily practice. A coach can create the right environment to guide the player who is trying to be better. A player with poor command likely focuses too much on not messing up, creating a self-perpetuating cycle. Focus on drills that do not discipline failure but instead reward success. The latter can be applied simply by giving the best pitcher in the drills, scrimmages or competitions each week some team gear or other incentive, rather than making everybody who loses run. If the focus of the drill is to not mess up, athletes will instinctively only attempt to avoid trouble. But if the focus is to win, an athlete will figure out a way to get that win.

If a player hates being at practice and has a negative coach or team environment, it’s unrealistic to expect positive outcomes. If a coach’s style is based around punishing failure, “tough love” and yelling – it might make sense to avoid recruiting pitchers who don’t fit into that system – i.e. the perfectionists and other personality types we’ve already discussed.

Final thoughts: Players

To improve command, a player’s energy should not be focused on being emotionally involved with thinking about mistakes or other bad practices. In other words, the extra 10 practice balls you threw because you did not like your performance likely does more harm than good, which is another reason it is important to track improvement over time. Don’t focus on week-to-week fluctuations while you are maintaining a regular schedule with a set amount of total throws. Self-conscious reinvestment was found to be a personality trait linked to focal dystonia (Bennett, 2016). Reinvestment can be summed up as those moments in practice where you keep saying “one more” 20 extra times because you didn’t like the outcome of the last pitch.

Other personality traits include perfectionism and self-critical internal thinking, all of which were found higher in Yips/LMS subjects than control subjects. Perfectionism can be an admirable trait to have, but when a perfectionist is also highly self critical, he is distracted by unnecessary thoughts which make it more difficult to properly organize the nervous system to throw a strike.

So to summarize again; if you finish a bullpen and it’s a bad day, do not throw extra pitches as a way to ‘fix’ the bad performance. The caveat to this is that an extra 3-5 pitches is probably acceptable, depending on the reason why — for instance, if you had a good feeling about the pitch before and wanted to try and repeat it. The times you want to avoid are when you keep getting mad at yourself and go beyond your previously set limit out of anger/negative emotion. If you don’t have a great bullpen, just let yourself have a bad day and forget about it tomorrow. This is similar to how some artists step away from a project for a little while to focus better when they do return. Your brain will go to bed and naturally try to make your proprioception better. So don’t go to bed angry, instead what would help more is if you just say a prayer thanking (whoever) because you got to play another day of baseball and get back to work with a fresh day.

Suggestion for Mentality on the Mound

Baseball is a game of failure, and brushing off a pitch that wasn’t executed well is important to throwing the next ball with conviction. To avoid being rattled, many elite players develop a mental routine to clear their mind, focus in on the present and block out unnecessary emotions/stimuli. Remember, (Milton, 2007) was able to pick out novices from the elite 6/6 and 7/7 times respectively by examining basal ganglia/limbic activation through fMRI data. Milton went on to discuss that this is a function of the amateurs not being able to filter the irrelevant stimuli.

The mental routine you should take to be consistent is the one that works best for you, is clearly defined and is repeatable. As a suggestion, instead thinking about perfectly placing the ball, think about throwing with conviction and trusting your preparation. Furthermore, the mental routine should also include your physical pre-pitch routine – how you toe the rubber, how you come set, and how you take the sign from the catcher are all physical anchors that will ground you in a more stable mental state. Once you have taken the sign from the catcher, a mental process might look like this:

- Focus on throwing the pitch with conviction and intensity.

- Take a breath, let the muscles in your face completely relax, look straight ahead but do not focus on the exact spot you want to hit

- Start your motion preparing to throw as hard as you can. Avoid tensing up too early in the throw.

- Pick up the target as you begin to come out of your leg lift. Use a rhythm and timing that feels natural to you.

- Throw gas.

- Flush the result of the pitch (good or bad) and repeat.

Note: some pitchers do fine staring at the target the entire time – but like Kershaw noted above, he still avoids allowing the location to take up the majority of real estate in his mind as he executes the pitch.

Don Cooper has his own version of this mental rehearsal, essentially focusing on the same nuts and bolts: intention, trust and flushing the result (good or bad):

Why You Can Overcome the Yips

To conclude, helping the yips affected player is a matter of getting the player to “clear his mind”. There is no “best” solution. The yips are far from being understood because it is presently very difficult (but not impossible) to find out how the brain’s neuro-functions are working inside a player’s mind. That does not mean we must be completely pessimistic about solving an individual’s yips. Yes, yips might be a daunting task you have come to believe you cannot overcome and might even get worse. However a study at Kyushu University, Japan, examined players who overcame the yips and grew from the experience. The research surveyed 416 university level baseball players who either had the yips, overcame the yips, or never experienced them. Using the “Psychological Maturity as an Athlete Scale”, the group that overcame obtained higher scores in self-understanding, had greater focus on independent achievements and goals, rather than focusing on teammates, and gained a clearer understanding of what baseball means to them. Some baseball players have overcome the yips completely on their own and gone on to successful baseball careers (Matsuda, 2018).

It’s important to remember that players have overcome struggles with the yips by themselves and continued to play baseball.

Conclusion

The primary purpose of this article was to systematically review the psychological, neurological and physiological parameters of the yips along with the impact the yips have on performance. After exploring the causes of the yips, together with the way it manifests itself in an athlete’s mind, I believe it is possible to extrapolate research from other sports to understanding the yips in baseball. I defined the yips as a form of task specific focal dystonia that results from a shift from external to internal thinking, leading to the breakdown of the basal ganglia and the functions controlling proprioception. Despite the yips being considered an individually inflicted issue, where the player is mentally weak and unable to handle pressure, I conclude the yips are much more a product of a player’s environment than previously thought.

What I am currently investigating

I am currently doing research using EEG sensors to look for evidence of neurological differences between players with and without the yips. My initial focus will be mapping whether different types of throws produce neurological differences. For example, throwing with eyes open versus eyes closed will be one of the first experiments. My goal is to find and connect differences in neurological activity to different levels of player control.

I will be doing this research with Bobby Tewksbary in Nashua, New Hampshire, and I am excited about where this research may lead. By looking for conclusive data into where the yips comes from I am hoping to unravel clues as to how to fix the issue — or at least find better ways of preventing it.

Glossary

YIPS: A physiological and neurological breakdown inside the mind of an athlete. In baseball this looks like a thrower not coming close to a target.

TYPE I YIPS: Neurologically Based

TYPE II YIPS: Psychologically based form of “choking”

FOCAL DYSTONIA: When muscles cannot perform a task manifesting itself with locking limbs. Seen in golfers, writers, musicians.

BASAL GANGLIA: A group of structures in the cerebral hemispheres including the brainstem (part of brain attached to spinal cord). While nonmotor functions are also associated, the structures are best known for their role in movement. The role in movement is to influence activity in other areas of the brain.

MUSCLE INHIBITION: When the muscle is activated, also known as the muscle reflex, and a relaxation of an antagonist muscle. Seen often during a dynamic stretching warmup where one muscle is activated while another is stretched.

LOST MOVEMENT SYNDROME (LMS): Essentially the same as the yips but is the term used in the research for artistic sports like divers and gymnasts.

THE FROST MULTIDIMENSIONAL PERFECTIONISM SCALE: The most widely used measures of perfectionism.

fMRI: Is a functional MRI where brain activity is measured by detecting changes in blood flow. Relies on fact that blood flow and brain activation of a region are coupled.

To learn more or get any other questions answered by Nick, send a message to his email: bugsyjagger@gmail.com