by Ben Brewster

This article is part one of a two part series on reasons an athlete’s velocity might fluctuate in-season. (Note: These factors contribute to off-season fluctuations as well.)

—

A growing percentage of the baseball world, which has traditionally held that velocity is “God-given,” is now investing in velocity development. Strength training, weight gain shakes, long toss, radar guns and weighted balls. These are the tools being increasingly used to prepare the new crop of arms to take the mound. Still, many athletes don’t understand the complexity of what goes into setting a throwing velocity record – and why it’s simply not feasible for a pitcher to have his A+ stuff every single time he toes the rubber.

Most pitchers can separate their outings into three categories:

A game – This occurs about 10% of the time. You feel like a million bucks and your stuff is electric. If only it were always like this.

B game – This occurs about 80% of the time. You feel decent. You don’t have your lights out stuff, but if you focus and compete, you’ll be just fine.

C game – This occurs in about 10% of outings. You feel zombie-like, your arm moves like a slug and you need to dig deep and compete with what you’ve got.

The big question is why can’t we perform at our peak more regularly? And, when a sudden dip in velocity occurs, is it reason for alarm?

Let’s dive into my top reasons why your velocity is going to have its ups and downs.

—

1. Cumulative fatigue from throwing

This is one of the most common reasons for massive velocity fluctuations – an improperly managed total throwing workload (taking into account both number and intensity of throws). Insufficient throwing workload can lead to an under-training effect, such as the pitcher who only throws on the day of his weekly start, whereas excessive throwing workloads lead to an overtraining effect and leaves the arm and body in a perpetually fatigued state.

Keep in mind, total throwing workload isn’t just live game pitches, it’s warm-ups and practice throws as well. An example is the relief pitcher who may only throw 3 one-inning outings per week (~50 pitches), but is also throwing 30-45 max effort warm-ups in the bullpen before each outing (another 90-135 pitches), in addition to his pre-game/practice throwing 6 days per week where he gets overly aggressive on many of these days as well.

The stress/adaptation response requires a stressor (throwing), followed by sufficient time to recover from that stressor and allow the body to adapt. Much like we can’t max out a muscle in the weight room every single day, we can only recover from so much throwing-specific stress.

If your arm is hanging and your velocity is fluctuating, take a close look at your total throwing workload.

—

2. Cumulative fatigue from lifting

If you aren’t continuing to strength train in-season, you should be. While you’ll get away with not training for a few weeks before noticing a decline, this isn’t a good long-term strategy for maintaining your velocity late into the season. On the flip side, you’re unlikely to maintain your performance if you continue training at off-season workloads, which are geared towards building strength + size, not maintaining strength while maximizing performance.

Here’s our take on how to adjust in-season training volumes – hint: cut your number of sets in half and maintain 90% of the regular weight used.

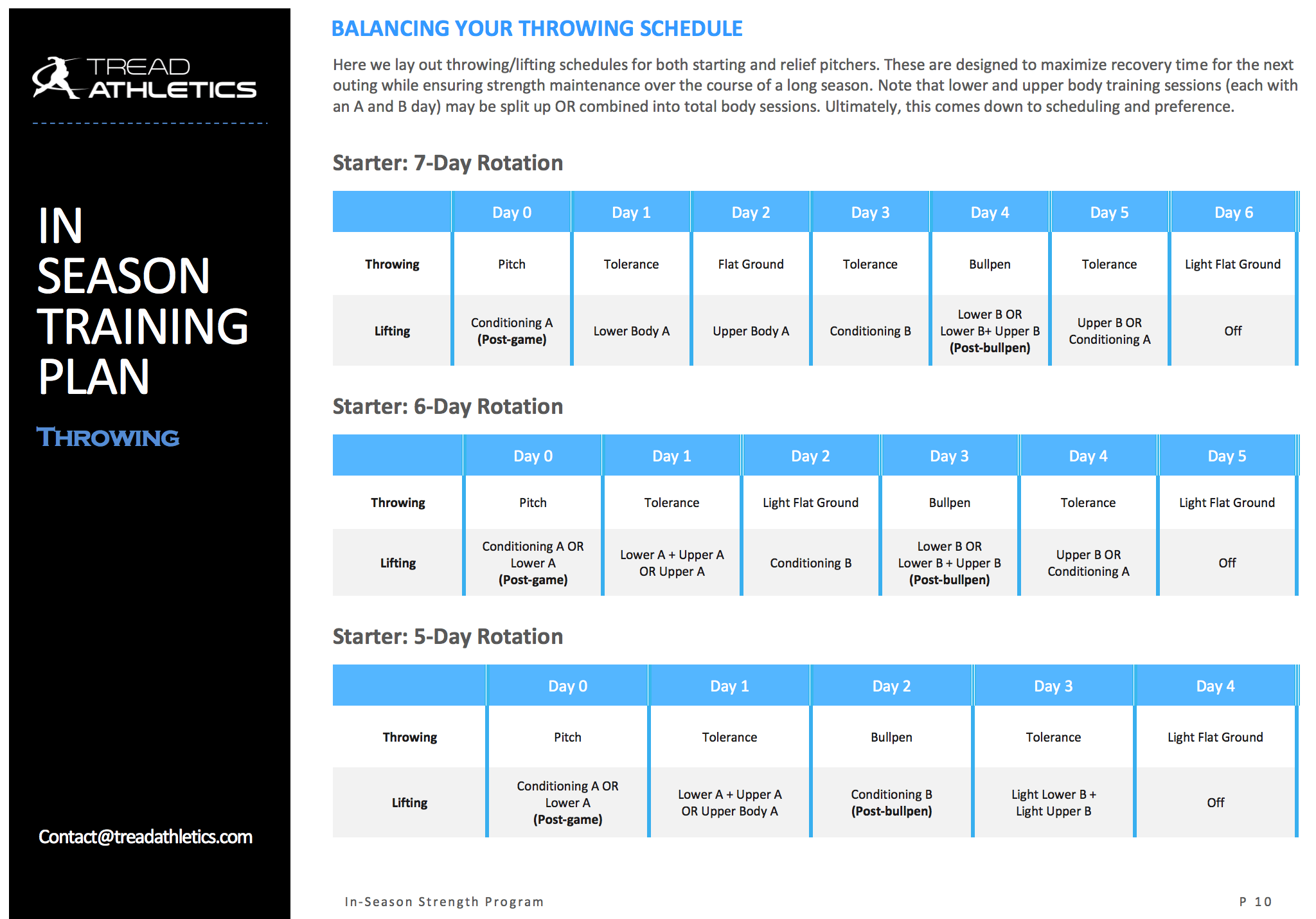

Timing of strength training is also important in-season – schedule your 2-4 in-season lifts around your outings so that you aren’t crushing lower body the day before a planned outing, for example. This varies quite a bit based on starter vs. reliever, 5, 6 or 7-day rotation, etc. An example of how we plan this out is shown below:

If you are interested in checking this out further, you can download a free copy of our in-season training blueprint here.

—

3. Caloric Balance

Maintaining weight + strength is a two-part equation. As we just covered above, keeping a sufficient training stimulus is part one. Part two is keeping a sufficient caloric intake. Without sufficient calories, your body won’t have the raw building material to hold on to the muscle mass gained in the off-season.

Couple a sharp rise in energy expenditure in-season, with a 4 to 6 hour daily window when athletes are at the field and typically not eating at all, and this is a recipe for muscle, strength and velocity loss.

Consuming around 1,000 calories during this time (a pre-batting practice peanut butter sandwich, a pre-game granola bar and a mid-game protein bar, for example) is the best way to offset this. Just be sure you’re still hitting sufficient calories + meals the rest of the day, and regularly collecting bodyweight measurements to monitor any sharp weekly drops.

The other factor to consider is that after a day or two of being in a calorie deficit, even if noticeable weight hasn’t been lost, energy levels and mood begin to worsen (as muscle glycogen stores are depleted), which in my experience can certainly have an impact on in-game performance. Don’t skip meals, especially the days leading up to a game!

—

4. Macronutrient breakdown

To add on to the above, not only will insufficient calories lead to weight/strength loss, lethargy and possible velocity dips, but the breakdown of these calories can play a role as well.

Protein

Protein intake is crucial, as it plays a key role in muscle recovery and strength maintenance – too little protein in the diet, and the body will begin to dip into its own protein stores (muscle mass!). Shoot for 1 gram of protein per day, per pound of bodyweight. For me, I shoot for anywhere between 200 and 230 grams per day.

In-season, and with travel, getting sufficient protein from fast food type restaurants can be a struggle. Supplementing with a few scoops of Whey protein per day, or remembering to ask for double meat on your Subway sub or Chipotle bowl are useful tweaks when traveling.

Carbs

Carbohydrates are your body’s preferred energy source during moderate to intense exercise, and they come in two forms: simple and complex. Simple carbs are your quick-acting sugars – keep these as low as possible in all but the pre-game/pre-workout window. Complex carbs, or starches, which provide a sustained release of energy, should make up the bulk of your carbs. Potatoes, rice, bread – eating enough carbs usually isn’t an issue, but if you reduce your intake too low, it can lead to low energy, decreased endurance and decreased performance.

Fats

Completely avoiding fats isn’t a good idea either, as fat intake plays a role in maintaining testosterone levels and general hormonal balance. Most athletes have no trouble getting saturated fats – from greasy burgers or dairy, but struggle to remember to get unsaturated “healthy” fats from nut butters, avocadoes, and coconut/olive oil.

Snacking on trail mix/nuts on the road, or adding healthy oils to your meals at home are two easy way to cover your bases.

—

5. Weather/temperature

The first thing most pitchers do after an uncharacteristically low velocity day is to freak out. Oftentimes, the elements play a role. Extreme cold or hot, wind, and especially rain, will have an effect on day-to-day velocity fluctuations.

—

6. Mound conditions/specifications

Many pitchers notoriously throw harder outdoors than indoors. This tends to be due to improved traction with cleats on a quality clay mound vs. a turf indoor mound. Anything that improves traction will tend to improve the ability to transfer force through the ground off the back leg, and effectively stick the landing to transfer force through the front leg up the kinetic chain.

While throwing outside tends to elicit higher velocities, loose dirt mounds, or worse, muddy conditions, are a pitcher’s worst nightmares from a velocity standpoint.

The height of the mound plays a role as well – don’t expect to see perfectly uniform, manicured clay mounds until you reach the upper college or professional levels. Taller mounds tend to elicit higher velocities than shorter mounds, but the magnitude of this effect does seem to be dependent on the individual. Pitchers with more north-south mechanics (see Sandy Koufax below) seem to benefit more from a large slope than lower arm slot, east-west pitchers (i.e. Randy Johnson). This is purely anecdotal, but it makes sense in terms of matching the plane of rotation to the slope of the mound.

For Part 2 of 2, the next six reasons an athlete’s velocity might fluctuate, check it out here.

—

Looking to learn more about the nuts and bolts of training a pitcher for strength and size? Check out Building the 95 MPH Body.

Questions or comments? Leave your thoughts below, or email us at contact@treadathletics.com