This article is part two of a two part series on reasons an athlete’s velocity might fluctuate in-season. (Note: These factors contribute to off-season fluctuations as well.) Check out part one here.

—

7. Time of Day

There is evidence that trying to peak within the first 4 hours after waking, specifically early in the morning and when athletes haven’t been accustomed to such early competition, may significantly reduce performance.

Scientists have suggested this may be linked to core body temperature, which takes time to build up to optimal levels after waking. I’m sure it’s linked to the following factor as well – physiological arousal. Don’t be surprised if your velocity is down a couple ticks if you throw an early morning game or bullpen into the mix – this is relatively normal.

—

8. Physiological arousal / stimulants

Higher arousal kicks us towards the sympathetic nervous system (the fight-or-flight response), which involves a hormonal cascade that increases adrenaline and cortisol, raising heart rate and potentially motor unit recruitment. Think yelling and smashing a beer can against your forehead or getting a slap on the back before a big lift.

Lower arousal shifts us the opposite direction, towards the parasympathetic nervous system (the “rest-and-digest response”), which slows the heart rate and allows for more control over fine motor tasks. Think taking a deep breath with a slow exhale.

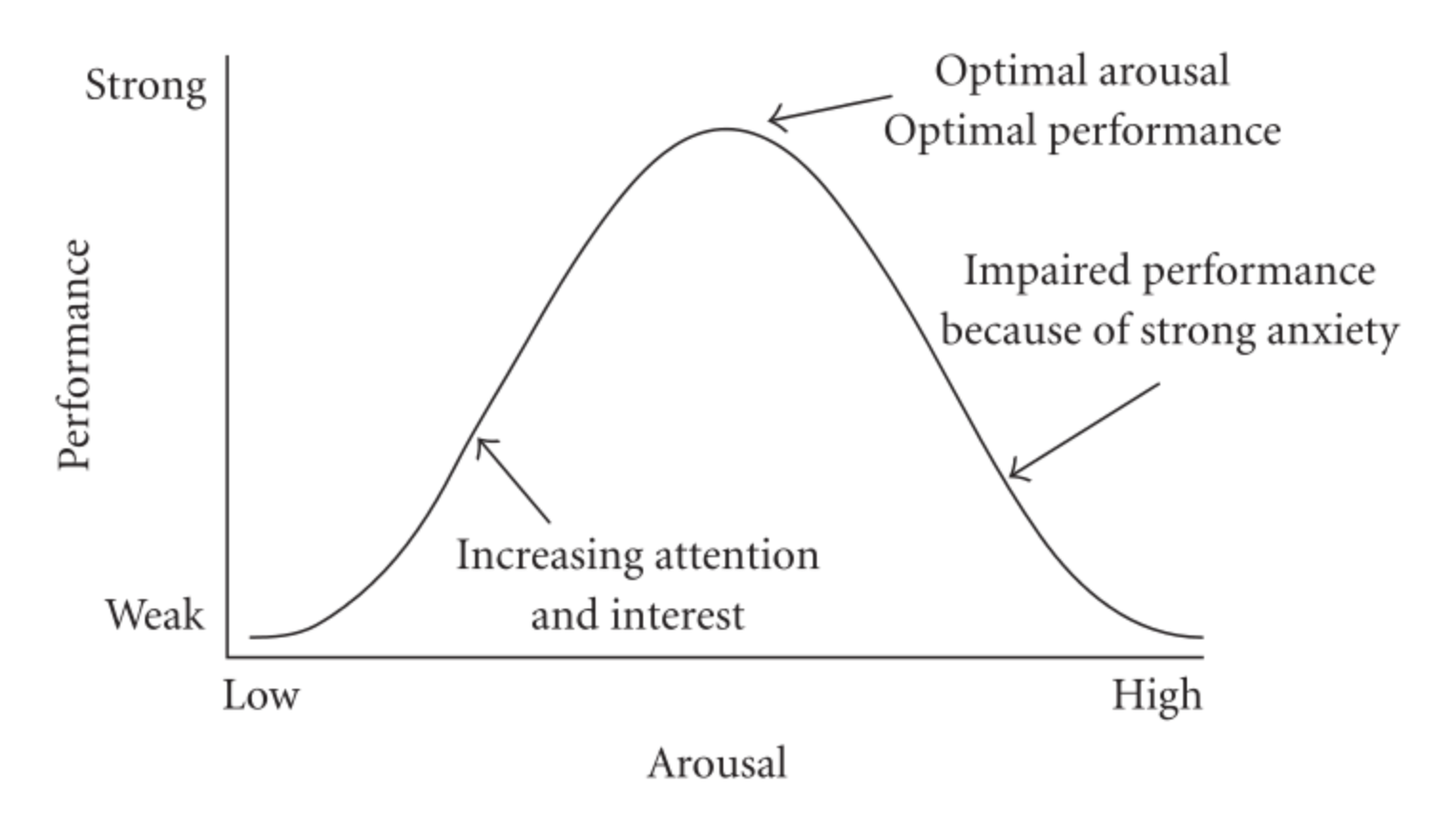

A key takeaway here is that different tasks require different levels of arousal for peak performance, but there is a bell curve relationship where both too little and too much arousal will reduce performance.

The Arousal vs. Performance bell curve

Rolling out of bed and yawning before you throw isn’t optimal, and neither is pounding 7 red bulls so that you can’t think or relax enough to repeat your delivery.

If your arousal is shifting all the time – afternoon vs night games, scouts vs. no scouts in the stands, home vs. away – this can often explain fluctuations in velocity.

Each guy is different too in what level of arousal works for them – the intensity of ‘Mad Max’ Scherzer (shown below) vs. the focus of Dallas Keuchel, for example. The point here is to know yourself – which takes time, and once you’ve determined what the optimal level of arousal is for you, work to replicate that psychological, and in turn, physiological response each time.

Many guys gear up for scout day, hit a new high velocity, and then fail to ever get themselves into that mental state for scrimmages or bullpens, scratching their head why they can never peak like that again. In these types of cases, lower arousal may be a culprit.

A note on stimulants – they can be helpful in moderation, but be careful.

For me, I had to actively avoid stimulants in high-energy game environments – 5,000 fans provided plenty of natural arousal – and artificially adding it put me over the edge. If your hands are shaking uncontrollably, there’s a sign you’re a bit too amped up to repeat your delivery with any precision.

To go along with this, relying on stimulants everyday builds a tolerance and can lead to issues and reliance over time. If you are going to use caffeine and energy drinks (which can definitely serve a purpose), save it for a couple days a week when you need it to avoid this adverse effect, and make sure not to use it to mask poor recovery habits.

You guys are going to ignore this warning until you learn the hard way, but I figured I’d put it in here nonetheless so I can say I told you so.

—

9. Sleep quality / travel

Often related to crazy travel schedules in-season, sleep is a precious commodity. I can recall multiple times my first year of pro ball where we would finish a late game, and an hour later begin a 12 hour trip through the night to our next destination only to catch a couple hour nap before needing to be at the field again the next day.

The deleterious effects of poor sleep on performance are many, and can occur even without crazy travel schedules if you begin to slack off and let bad nights of sleep stack up. Don’t be surprised if you’re a tick or two down on the radar gun after a night of tossing and turning, especially if you took sleep aids or alcohol which can reduce the amount of high quality REM sleep actually obtained during these precious hours.

—

10. Fluctuations in mobility

Less common, but still worth noting, are mobility fluctuations. After the acute stress of throwing, highly stressed muscles temporarily shorten as they recover. For example, this increased tone can occur in terms of temporary lost shoulder internal rotation (as the posterior cuff recovers), forearm supination (as the pronator flexor recovers), shoulder flexion (as the lat recovers) and horizontal abduction (as the pec recovers). This is one reason, along with the cumulative fatigue from throwing, that velocity tends to decrease on day two or three of consecutive live outings.

This isn’t surprising – for example, nobody was shocked when Brandon Morrow (pictured below) was throwing 94 instead of 100 mph by his 7th outing in 7 World Series games this past year.

Despite an apparently bulletproof UCL, even Morrow’s cyborg arm drops in velocity after insufficient recovery.

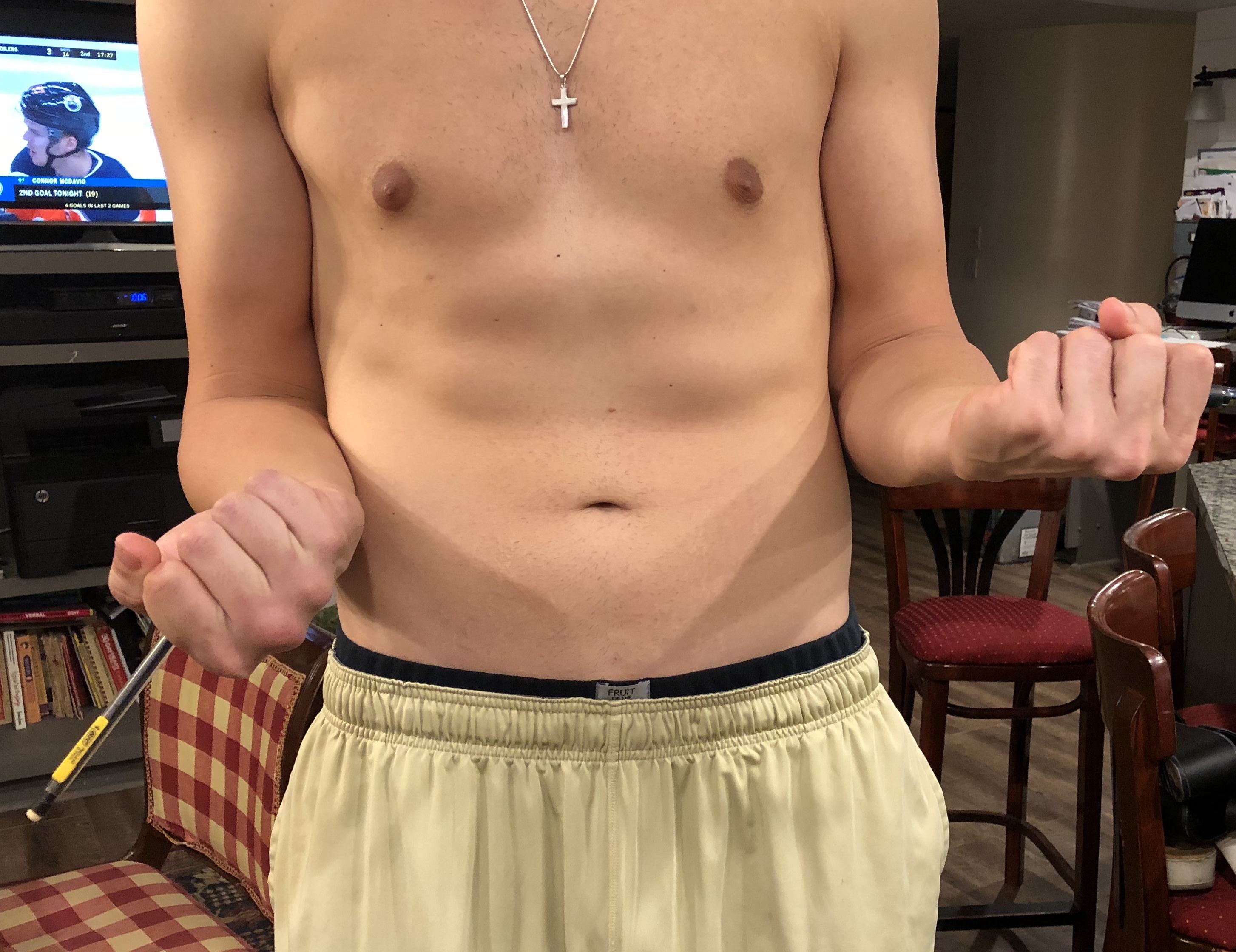

Fatigue is obviously a big factor, but understand that temporary losses in mobility play a role as well, and that these losses can become semi-permanent if left unaddressed for months or in some cases years (which is why you see some gnarly adaptations in most pitchers related to the mobility issues mentioned above). Below is one of our lefty pitchers doing an elbow supination comparison, showing just how much range can be lost over the years if left unaddressed. Not all adaptations are negative, but being aware of what’s happening in response to the workload being placed on the body can help with preventing such asymmetries from become symptomatic over time – or beginning to bleed into performance.

A lefty pitcher showing a more than 45 degree difference in elbow supination.

—

11. Inconsistent throwing focus

This is an often-overlooked factor in velocity fluctuations. Going into my first outing of pro ball, I had just come off a Super Regional game where I sat 93-94 mph. On this particular day, and despite sufficient rest, I found out after my first pro outing that I was 88-92. My arm had felt great, but looking back I realized that I had gotten away from trying to attack and throw the crap out of the ball as I had the week prior. I could have freaked out, begun overanalyzing my mechanics, etc…, but I simply shifted the focus back to what it had been all college season – trying to challenge and dominate hitters with my best stuff, not tentatively placing the ball into the strike zone. Lo and behold, the velocity was right back where it should have been 2 days later, and I was promoted from Rookie ball the next day.

It’s very hard to consistently produce your best fastball if you only allow yourself to focus on your best fastball when you think it matters – scout day, off-season velocity testing, etc. Being able to lock down the focus and mentality that elicit your best days is a key aspect to having more of these types of days.

—

12. Mechanical repeatability

I hate to say it, because talking about mechanics, especially in-season, tends to be a performance nightmare. Overthinking where your body or limbs are in space, changing mechanical cues on a daily basis, or getting your ear talked off in between bullpen pitches by a well-intentioned coach are guaranteed ways to leave performance on the table.

That being said, if your landing spot, release point or hip/shoulder separation are varying wildly from pitch to pitch our outing to outing, it’s going to have an inevitable impact on your velocity.

Now, if you’re in season, that last thing you need to do to fix this is work on mechanics (if you’re in off-season velocity training, that’s potentially another story).

If you’re in-season, improve your mechanical repeatability by focusing on routines.

No, I haven’t gone off the deep end. Routines are the single reason that, despite the most god-awful mechanics (which were seemingly changing every week my first few years of college), I was still able to compete and repeat with any shred of consistency.

Routines could and probably will be an entire article to themselves, but I’m speaking specifically about three routines: your Pre-game routine, your Pre-outing/bullpen routine, and most importantly, your Pre-pitch routine.

Pre-game routine

This connects to many of the earlier points in this article, but it’s important here as well. What time do you get to the field? What do you do when you get there? How long does that take? At which moment do you turn off your phone? How long does your mobility work take? When do you begin warming up?

These are all details that big leaguers have down to a science. If you’re just taking the days as they come, you’re not doing it right, and you reduce your chances of repeating a consistent delivery.

Kershaw in his “Bro Tank” doing shadow work before a playoff start.

Pre-outing/inning routine

If you’re a starter, when does your pre-game bullpen begin? How many pitches? In what sequence? In between innings, where in the dugout do you sit? What’s one word or breathing technique you use in between innings to stay focused?

If you’re a reliever, what inning do you head down the bullpen? What inning do you begin warming up? What inning do you begin tossing in case you’re called? What’s your bullpen sequence under ideal and “rushed” scenarios?

These details matter, so you’re prepared for whatever comes during the game.

Pre-pitch routine

Repeating your mechanics becomes leaps and bounds easier when you have a pre-pitch routine. The reason for this is that your psychology has a huge impact on your physiology. Putting yourself in the same mental state before each pitch gives you the best chance to put your body into the same physiological state, and repeat your delivery from pitch to pitch.

Don’t believe me how important routines are?

Watch any college basketball or NBA player shoot a free throw.

You don’t see randomness. You see the shooter set up at the exact same spot. Pick up the target at the exact same time. Dribble the ball the same number of times, and take a deep breath, perfectly on cue. It’s a relatively simple motor pattern compared to throwing a baseball, but basketball figured out long ago the importance of routines on performance. Check out Steve Nash (below) talking about how his routine made him a great free throw shooter.

Imagine how important this principle is for repeating such a complex movement as throwing.

In college, we devoted real practice time to pre-pitch routines. There was no ball, and we weren’t even working on full dry reps – just rehearsing the routine of getting the sign, coming set, taking a deep breath, repeating our personal keyword or mantra (“attack,” “loose,” “quick,” “f#%k you,”), and delivering the pitch. We did this for 5 to 10 minutes most practices – far more useful than running daily poles to fill time as most pitching coaches turn to.

On the road in college, we would do this Thursday nights on the opposing team’s game mound, lining up to get our mental reps in.

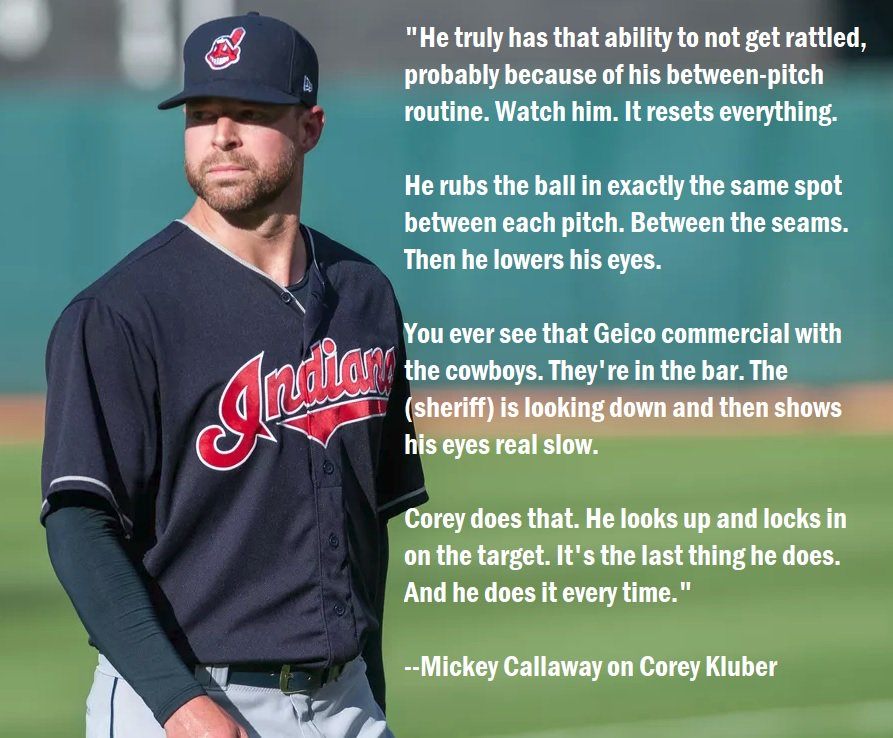

Still not buying it? Here is a quick take from former Indians’ Pitching Coach and current Mets’ Manager, Mickey Callaway, on Corey Kluber’s routine between pitches.

Corey Kluber is a great example of a player with an elite pre-pitch routine.

Most of you will gloss over this final point, but it’s perhaps the most important recommendation in this entire article, so ignore it to your own detriment.

—

Conclusion: Don’t freak the f$%k out.

There are many reasons your velocity will fluctuate in-season or from bullpen to bullpen. Some fluctuation is perfectly normal. In no scenario is freaking out and jumping ship on your program the right move. This will be your gut reaction, so just recognize that’s an urge you’ll have to suppress.

Take these recommendations into consideration the next time you drop 2 miles per hour and think the world is going to end – more times than not, the answer will be staring you right in the face.

Make the logical adjustment and get refocused for the next game.

Every day is a new chance to prove yourself.

—

Looking to learn more about the nuts and bolts of training a pitcher for strength and size? Check out Building the 95 MPH Body.

Questions or comments? Leave your thoughts below, or email us at contact@treadathletics.com