by Ben Brewster

I wanted to give my take on a very common question we get from our athletes: how the hell do you learn to use your back leg? This is something I struggled with FOREVER, and held me back quite a bit in my career because I had no idea how to initiate motion towards the target and be able to transfer that into the upper half. Here are some of the biggest tips, cues and drills that have worked for me. I hope you find this useful.

Enjoy!

—

Q: I have a hard time using my lower half when I throw. I really don’t know how to drive with my back leg. I think the main reason is that whenever I try to drive my back leg, the momentum of my back leg tends to go up instead of going to the direction I throw, so I lose a lot of power. How do I fix this?

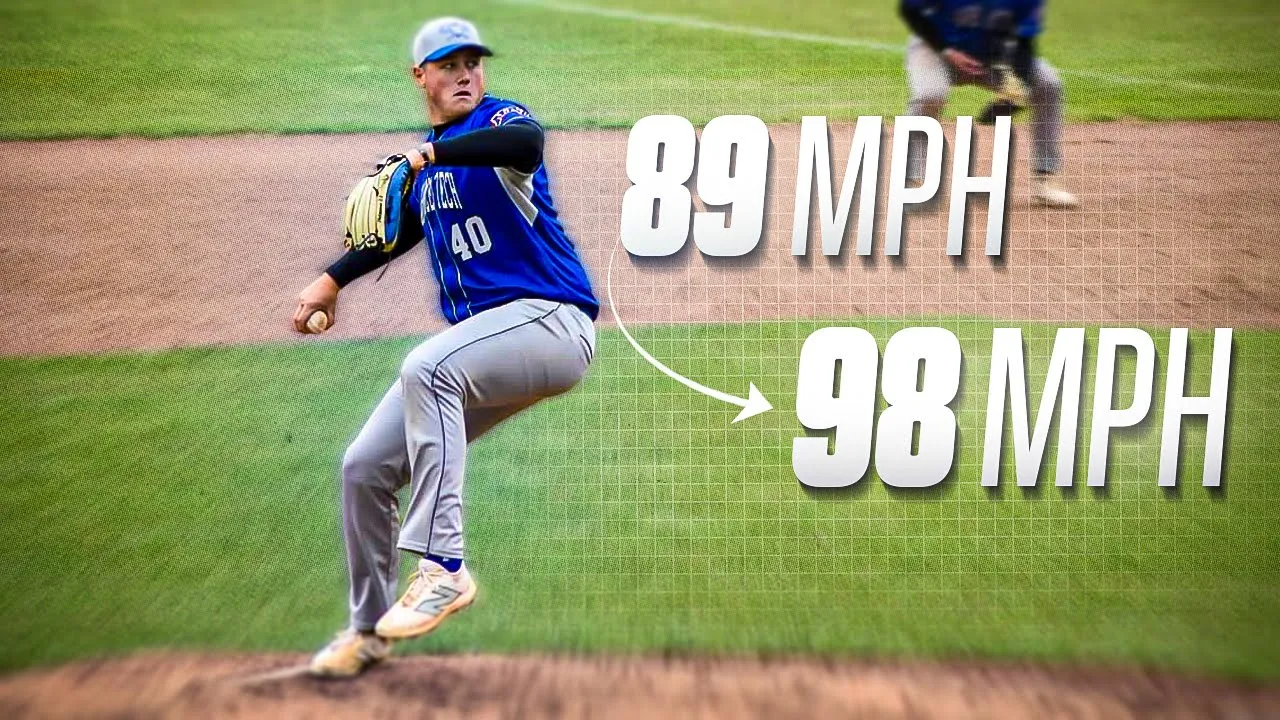

This is something I struggled with for a long time as well. After finally learning to use my back leg (which really means learning to shift my weight properly) I jumped from 87-90 (t92) to 90-94 (t95). From that slide-step delivery, I then learned how to transition this even further to a full leg lift, and this got me to 96-97 (t98) in bullpens. I have had a strength base and good mobility for a long time, but it was learning how to transfer energy from the lower half and shift my weight properly that saw these massive spikes in velocity.

So here are the 3 things that helped me the most in regards to learning to properly use the lower half and, specifically, the back leg:

—

1) Focus more on driving with the rear glute rather than pushing with the quad.

The quadriceps muscle action is to forcefully extend the knee which will drive your center of mass upwards if that happens too early. Focusing on moving forward from the rear glute is a good first step – the quad will still activate, but that should not be the focus. It’s much more of a secondary isometric contraction that occurs during the drive phase, not the primary concentric contraction.

Even the poster boy for the “drop and drive,” crowd, Carson Fulmer (below), isometrically sits into his quad while gaining this forward motion from the glutes and hamstrings to extend and abduct the hip. Much like efficient sprinters don’t push the ground away from them, but rather, pull the ground backwards via the glutes/hamstrings, the most efficient pitchers incorporate this action into the frontal plane. Think “clawing” or “pulling” the rubber back towards second base, not “pushing” or “lunging” off of it. You can also look at it as pulling yourself towards the target, if that creates a better picture in your mind.

Even Carson Fulmer doesn’t rely on the quads as his main source of power.

Even Carson Fulmer doesn’t rely on the quads as his main source of power.

—

2) Learn to pre-coil the spring

What I mean by this is that if you want the lower half to drive horizontally and open into landing and the upper half to stay back and closed at landing, one strategy that worked for me is to set your position at peak leg lift to be the reverse of this movement. This means coiling the hips back against the upper half, which results in the unloading in the opposite direction as you come out of peak leg lift.

Roger Clemens is a good example of this. The upper and lower halves work against each other during the leg lift which sets up this smooth lateral and rotational unloading of energy.

Clemens turns and laterally tilts his torso against the hips, effectively coiling the spring.

So the back leg isn’t actively pushing down the mound, it’s better to think about it as “catching and accelerating” the center of mass via this “clawing/pulling” action. By the time you do get into the back leg, your center of mass should already be shifted such that you feel a sensation of hitting the “turbo boost” or “roller coaster.”

Muscling your center of mass towards the plate from over the rubber is not an efficient way to transfer energy, and starting pitchers wouldn’t be able to do that while maintaining their stuff for 100+ pitches if they were doing max effort lateral jumps.

Bartolo Colon wouldn’t still be pitching if he didn’t shift his mass effectively, because the amount of energy it would take to overcome that inertia would, quite frankly, be unsustainable. This is another reason many pitchers can get away with having a little excess “velo pouch” and a 15 inch vertical jump but can still throw very hard if they utilize their body efficiently on the mound. Once you’ve gotten the train moving, THEN it’s time to apply force from the rear glute/hamstring.

3) Do drills that help you feel a lateral loading up of the back leg.

To feel this, I recommend drills that start with your center of mass out front where you have to shift your weight back into your rear leg. Again, we’re using the idea of pre-loading the opposite of the pattern we want to create. Stepping back into the drill loads up the muscles in the exact opposite direction of how we want to use them, so from there it’s just a matter of reversing the movement from the back leg.

Examples of drills that accomplish this are:

- Step-Back Roll Ins (shown above)

- Properly done rocker drills

- Step-back wind-ups

Again, these are just some suggestions that worked for me.

And remember – the spine (and body) is built to transfer energy smoothly and segmentally. Try to feel smooth and fluid going through these drills – don’t stomp down on the back leg and immediately jerk forward – you should ramp up through these drills feeling like “the ball is throwing itself” or “the arm is along for the ride,” until you get up over 50% intensity. If you can get up in the 70s before actively applying any effort from your arm, you know you’re sequencing well. When I can throw low 80s during warm-ups (50%) feeling like my lower half is throwing the ball with absolutely zero effort from my arm, that’s when I know my sequencing is down and that I have 15+ mph left in the tank that day.

I wanted to include a couple more examples for you guys to see. There are countless MLB examples as well, but check out Matt Mercer (top, up to 100 mph) and me (bottom) to see how the leg lift sets up the lower half actions. Tim Lincecum when he threw 100 in college is another classic example, although he lost this dynamic lower half over the years.

At the end of the day, there are a lot of ways to teach and cue lower half actions. This is what worked for me, although keep in mind I’d had 7 years of coaches trying to teach the lower half with Towel drills, poorly cued Rocker drills and Hershiser drills, so take that for what it’s worth.

Good luck implementing these tips and here’s to reaching your potential!

-Ben

—

Looking to learn more about the nuts and bolts of training for velocity? Check out Building the 95 MPH Body, and visit our Remote Coaching Page if you’re interested in learning more about our top-end service.

If you have any specific questions you’d like answered in a future series, you can submit them here